“Our needs are different”: Refugee integration in ‘Steel City’ and perceptions of U.S. race relations

Yumeka Kawahara & Charlie Williams

In consultation with: Abby Jo Perez & Sohrab Saljooki

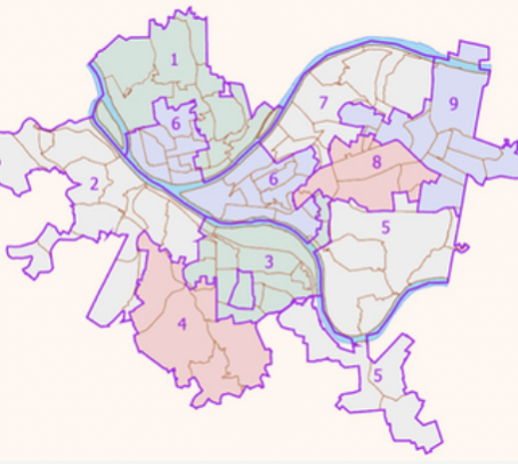

Location

This map illustrates Pittsburgh’s position in Pennsylvania, a state in the eastern United States. The United States refugee resettlement ceiling for FY 2022 is 125,000, a sharp increase from the last five years. The number of admitted refugees currently hovers around 25,465 individuals.[1]

[1] Migration Policy Institute. (n.d.). U.S. Annual Refugee Resettlement Ceilings and Number of Refugees Admitted, 1980-Present. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

Pittsburgh is a certified welcoming city – a city that has policies and programs to facilitate inclusion of immigrants – designated by Welcoming America’s network.[1] There are four resettlement agencies including: Jewish Family & Children’s Service (JFCS); Acculturation for Justice, Access, and Peace Outreach (AJAPO); Hello Neighbor; and Bethany Christian Services. Other migrant-serving agencies include Literacy Pittsburgh and Casa San Jose, among others. The city of Pittsburgh is part of a county-wide coalition called Immigrant Services and Connections in Alleghany County (ISAC), which aims to support refugee serving organizations in Alleghany County by connecting them with resources and communities.[2] Each organization serves a steadily increasing refugee population. For more background on refugees in the United States, see the appendices. Base map imagery © Google 2022.

[1] Welcoming America. (n.d.). Welcoming Network Directory. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

[2] Immigrant Services & Connections. (n.d.). Welcome to ISAC. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

Introduction

Much of the research on immigration and race in America only examines the ways in which immigrants and refugees experience racism in the US. However, relatively little research examines refugees’ understanding of race before they were resettled, and how this understanding shapes their experience of race and integration after they arrive in the US. This study aims to fill this research gap.

In 2022, the Refugees in Towns (RIT) Project at the Fletcher School partnered with the Hello Neighbor. Hello Neighbor, founded in 2017, is an organization made up of both a local program in Pittsburgh as well as The Hello Neighbor Network (The Network). The Network is a coalition of grassroots organizations in the United States dedicated to serving refugees and immigrants. Motivated by conversations among their members, The Network was interested in researching how refugees learn about US race relations in order to develop more extensive, anti-racist, and culturally informed resettlement orientation programming. The RIT team conducted qualitative research during the summer of 2022 in support of this goal.

This case study was completed with Hello Neighbor’s local program in Pittsburgh. Hello Neighbor offers mentorship programs, support for pregnant and new mothers, tutoring for school-age children, and refugee resettlement. Hello Neighbor’s enthusiasm to better serve their clients energized our research. To them, supporting an increasingly diverse community in Pittsburgh meant understanding refugee needs by hearing refugee perspectives and voices.

Research Question

Racial hierarchy is deeply rooted in the United States’ history. The country’s central role in the transatlantic slave trade underwrites contemporary structural racism. Additionally, Whiteness remains at the pinnacle of the US’ racial hierarchy, despite the country’s long history of immigration. Migrants, including refugees, have historically experienced the effects of this racial hierarchy. Additionally, because their (home) countries of origin have varying categorizations of race and racism, refugees may not recognize their home country racial norms as “racist.” This can be problematic when refugees try to form meaningful connections in their new neighborhoods because what was perceived as socially acceptable back home takes on new meaning in a different context. Accordingly, this study uses the term “race” to refer to ethnic groups, skin color, or nationality depending on the context of each interview, since for many participants “race” was a compounded term with several definitional variations.

Through the collection of 24 semi-structured interviews, this case study explores how refugees view Pittsburgh and how refugees navigate US race relations in this post-resettlement context.

Methods

In order to examine how refugees view Pittsburgh overall and how they navigate race relations in this post-resettlement context, we recruited and interviewed refugees, humanitarian parolees, and Special Immigrant Visa holders (SIVs) in Pittsburgh, mainly using the local community networks of Hello Neighbor staff. In this resettlement context, refugees are people who escaped from war, conflict, violence and persecution in their home countries. Humanitarian parolees are noncitizens who applied for temporary US admission for urgent humanitarian reasons. SIV is a status reserved for people who worked with the US armed forces in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Prior to the interviews, to familiarize ourselves (Charlie and Yumeka) with the city and its denizens, we explored some of the 90 neighborhoods that make up Pittsburgh. With the hope of building community trust, we also volunteered at events, including Hello Neighbor’s Study Buddy event, Islamic Center of Pittsburgh’ food distribution, and the World Refugee Day celebration. To better prepare for the interviews, we consulted with community consultants, Abby Jo Perez and Sohrab Saljooki.

Following recruitment and following the IRB verbal consent process, we engaged participants in semi-structured, conversation-style interviews. We conducted group interviews with several participants, often families. In most cases, interviews took place in participants’ homes, though some interviewees made requests for other locations such as cafes or the Hello Neighbor office.

We recorded participants’ responses and other observations, such as the participants’ body language, tone, and environment where the interview took place. We ensured that conversations stayed within the general themes, topics, and framework of the information provided in the interview guide (cleared with Tufts IRB). Interviews typically took 40-50 minutes and at their conclusion were transcribed with Microsoft Word’s dictation feature within at least one day for later analysis. As with all qualitative and exploratory research, our results cannot be generalized to broader refugee populations, either in our case study city or the wider US.

Our study completed 24 interviews. Respondents included 12 men and 12 women: 14 Afghan, 9 Congolese, and 1 Rwandan. On average, respondents had spent a total of 2.95 years in the United States and had a mean age of 32.3 years.

BOX 1: Community Connections with Guidance from Sohrab

One of our key informants was Sohrab, an intern who worked at Hello Neighbor, and who was very helpful to us during our time in Pittsburgh. He shared his perspective on the RIT-Hello Neighbor partnership.

I would personally consult with the RIT team on interpersonal relations with Afghan refugees, as I am a member of this community. I explained relevant body language for greetings and goodbyes and made sure they knew some basic Farsi. I also suggested that they follow cultural practices. In Afghan culture, it is common to bring a gift to those that open their homes for guests, so I recommended Charlie and Yumeka arrive with sweets that compliment tea because tea is a universal tool for socialization in Afghan culture. The topic of gender relations in Afghan refugee households was a touchier one, as it is customary for women to cover up as much as possible. I instructed them to be respectful of the family's wishes if they find an issue with how they dress, but not to worry too much. Afghan families that reside in the United States are often less strict about dress code for women and tolerate western standards of dress. My knowledge of Afghan customs is derived entirely from my lived experience.

On the interview itself, I informed the team that Afghan refugees and immigrants are not too fond of talking about things that are “political,” such as race. However, many Afghans can find specific issues personal enough to passionately discuss them. I referred to these “wedges,” where long conversations can make people more willing to open up about their opinions, and when they do they are much more open to discussing more difficult topics. Afghan families are more comfortable in a conversational setting with multiple people, so they would be less successful talking one on one instead of in a family/social setting.

-Sohrab Saljooki

The Authors’ Positions and Experience in Pittsburgh

Yumeka Kawahara

I am an East Asian woman (Yamato ethnicity) from Sapporo, Japan, and spent most of my life there. While Japan is a homogeneous country, I was exposed to various cultures through travel since I was a year old. I lived in Paris, France from 2019 to 2020 for my studies, where I experienced COVID-induced racism and had to hide that I am from Japan (or East Asia) to avoid discrimination. Moreover, I worked with refugees in Paris during my stay but had to leave them behind and go back to Japan as the COVID-19 pandemic worsened. This experience made me realize what it really means not to have a safe home to go back to, and strongly impacted my thoughts on racism and being a minority in society. In August 2021, I moved to Boston, USA to study refugee integration processes and the role of NGOs. In this study, I was aware that my own opinion on American racism could affect participants’ answers, therefore I paid close attention to being as impartial as possible during interviews.

Charlie Williams

I am a US-born, White woman from California’s Central Valley region. I grew up influenced by Western economic and educational models and privilege. While not an immigrant myself, I did grow up with stories about my great-grandparents who came to the United States in search of opportunity. I have intercultural living experiences from studying abroad in Spain and working briefly in Senegal. My work in Senegal was influential on my desire to work towards a decolonized mindset and adopt an accompaniment philosophy in my vocation. I feel connected to this research and its aims, as I hope to work as a practitioner in refugee resettlement in the future. I seek to better understand newcomers’ experiences in order to offer more equitable resources for refugees in the United States.

Abby Jo Pere

I am a US-born, white woman from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I have been a resettlement practitioner for the last decade in three northeastern US cities: Springfield, Massachusetts; Ann Arbor, Michigan; and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The roles I have had vary. I have been an ESOL teacher, AmeriCorps member supporting refugees, and resettlement case manager. In my current role, I am working to expand and further develop a culturally tailored program for pregnant immigrants and refugees to provide support, education, and advocacy while navigating the US birthing culture. Throughout my studies and professional roles in resettlement, one value has remained true: the spectrum of human experience is incredibly vast, but our similarities are stronger than our differences, evident when we pursue authentic relationships. This research is connected to me because just as my clients welcome me to be their sister, daughter, mother, or granddaughter - they are welcomed into my life as dear family members. My life’s work is to have a positive influence on the cultural orientation opportunities of new refugees, push for intentional inclusivity and anti-racist work, and make the US welcoming experience better for those to which it has historically not been kind.

Sohrab Saljooki

I am a Tajik Afghan and first-generation immigrant, born and raised in New York. During the summer of 2022, I worked as an intern at Hello Neighbor on The Network team. Currently I reside in Pittsburgh where I attend Carnegie Mellon University to study history and philosophy. I come from an extensive Afghan family background: my mother was born and raised in Kabul and my father was born and raised in Herat. My mother was forced out of Afghanistan in 1992 and became a refugee in Pakistan, later emigrating to Canada. My father emigrated to New York with the rest of his family in the early 90’s. Shortly after September 11, 2001, my family and I experienced Islamophobic discrimination at the Canada-US border which prevented our crossing. I would also be called a “terrorist” routinely in my K-12 schooling years. While personally never experiencing forced displacement, my upbringing can be defined by attempting to understand how that process shaped my family.

City Context

Population and Neighborhood

Pittsburgh is a mid-sized city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, with a population of 302,971 in 2020, of which 66.4% of residents are White, 23% are Black, 5.8% are Asian, and 3.4% are Hispanic or Latinx. As shown in Figure 1, racial diversity has increased significantly in Allegheny County in the past ten years.

According to county data, 26,254 refugees arrived in Pittsburgh between 2010 and 2019, including Bhutanese (9,378), Burmese (2,827), Congolese (2,939), Iraqis (2,470), Syrians (1,313), and Somalis (1,510). Since 2019, there has been an influx of Afghan refugees (in fall 2021) and Ukrainian arrivals in 2022. Pittsburgh was one of the 19 cities recommended by the US Department of State to resettle Afghan refugees. The various immigrant and refugees that call Pittsburgh home can be viewed in Figure 1 (provided by Welcoming Pittsburgh's 2021 Annual Report).

Figure 1.

Many people we spoke to described Pittsburgh as a city with “small town vibes,” with the feeling of a well-connected community. There are 90 unique neighborhoods that make up the larger Pittsburgh area, with most individuals living outside the downtown center. These neighborhoods were carved out of hills and sandwiched between rivers partly due to Pittsburgh's geography, resulting in communities with distinct cultures and feel.

Pittsburgh’s History of Immigration and Refugee Resettlement

Migrants of all backgrounds have shaped Pittsburgh. The city played a role in the French and Indian Wars and the American Revolution, which saw French and British settlers invade indigenous land.During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, European immigrants came to Pittsburgh motivated by a booming industrial economy. According to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette “Between 1880 and 1910, 17.7 million immigrants poured into America. [...] By 1910, Pittsburgh had become the eighth largest city in the United States, and 26 percent of its population was foreign-born.” Additionally, Pittsburgh was one destination of the Great Migration, when thousands of Black Americans from southern parts of the US migrated north. Many came to the eastern part of Pittsburgh in search of jobs: for instance, Carnegie Steel Company in Pittsburgh employed 4,000 African Americans in 1916.

Photo 1: Maxo Vanka, Immigrant Mother Gives Her Sons for American Industry (1937) - Vanka, a Croatian immigrant, created a series of murals like this one located in the St. Nicholas Catholic Church in Millvale, PA.

This history of migration shaped Pittsburgh into a diverse city with a history of welcoming immigrants and refugees. In turn, immigrants have contributed significantly: they paid $1.2 billion in taxes in 2019 with a spending power of $2.7 billion. The city makes efforts to integrate migrants. For instance, the Mayor’s office launched the Welcoming Pittsburgh Roadmap, “a citywide integration plan that includes civic and community engagement, education, language access, economic development, and sustainability as core themes, and which has forty leaders from diverse sectors, and over 3,000 community members.” Events are held to encourage mutual understanding between migrants and citizens, such as the World Square Market, World Refugee Day, and Women’s Way. These events allow participants to understand migrants’ culture through dance, food, arts, and storytelling

Egyptian artist performs at the Women's Way: Stories of Motherhood in the Time of COVID, a video showcase of refugee, immigrant, and US-born mothers’ stories. Photo by Charlie Williams

World Square Market promoting the Pittsburgh international community’s businesses and culture. Photo by Charlie Williams

“Pittsburgh Builds Bridges” by Ebtehal Badawi. We met her at the World Square Market event, which celebrates the diversity in the city and fosters mutual understanding between migrants and local citizens. Photo by Yumeka Kawahara

A Brief History of Race Relations in Pittsburgh

Despite a long-standing foreign-born population in Pittsburgh, the relationships between race, society, and belonging are complex and merit further attention, as historical attitudes and policies continue to impact people of color’s experiences in northern United States today.

Racial segregation and anti-Black policies were and are by no means limited to states in the Southern United States. While anti-Black laws and the systematic separation of people defined the Jim Crow South, policies rooted in racism across northern states continue to shape lives and communities today. Pittsburgh is no exception. Throughout the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, city officials consciously placed low-income housing out of the way on cheap land and utilized red-lining policies (such as the well-known Hill District). These and other policies contributed to economic and racial segregation in Pittsburgh neighborhoods.

“Urban renewal” and redevelopment, which often circumvented consultation with communities of color, are not limited to a bygone era. Pittsburgh still battles with the legacy and impacts of racist zoning practices. In our conversations with Pittsburgh residents, we were told about East Liberty, a neighborhood a mile from the Hello Neighbor office which some Pittsburghers of color call home. East Liberty currently faces redevelopment and gentrification in which local residents are priced out of their homes, and forced to move within and outside the city. For a city labeled as “the most livable in America,” we wonder, “livable” for whom?

Factors shaping race relations in Pittsburgh are not limited to housing policies. For instance, the city’s 2019 Gender Equity Commission report found that Pittsburgh’s Black women had worse outcomes in terms of health, poverty, employment, and education than other comparable US cities. Additionally, ten nationwide hate groups have chapters in Pennsylvania, four of which are active in Pittsburgh according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. While far-right factions and hate-centered activity are part of US history, extremist violence – motivated by racism, antisemitism, and xenophobia – is on the rise nationwide. Pittsburgh is keenly aware of this reality, illustrated in 2018 by the Tree of Life tragedy.

Tree of Life is a synagogue in Pittsburgh’s predominantly Jewish Squirrel Hill neighborhood. In its 150-year history, the congregation dedicated itself to service and tradition. In October 2018, an extremist attack occurred in which the congregation was targeted by a lone gunman who killed 11 worshippers. The gunman had made anti-Semitic comments online before the shooting, one of which falsely claimed Jewish people were responsible for transporting migrant caravans across the US southern border. A key-informant later told us that congregants were participating in a nationwide refugee Shabbat organized by the resettlement agency HIAS at the time of the attack. Tree of Life remains the deadliest anti-Semitic attack in US history and its legacy illustrates the penetrating impact of racism, xenophobia, and hate-based violence on communities in Pittsburgh.

BOX 2: A Bus Ride Through Squirrel Hill

As a research assistant in Pittsburgh living without a car, the bus became my best friend. With a two-hour commute every day, I had plenty of time to reflect on the city landscape on my way to and from participant interviews. One of my regular routes took me by a sturdy-looking building. Flowers and signs written by children hung on the outside. There were hints of deep love for this place. But for a building that seemed cared for by the community, the space also strangely appeared desolate. Empty. Hurting.

When I couldn’t handle my curiosity any longer, I asked one of my Hello Neighbor colleagues about that building on the bustling street corner which blankly stared back at me on those numerous bus rides. “Tree of Life,” they said, “there was a shooting there that really shook up the Jewish community in Pittsburgh. I have friends whose contacts were directly affected.” My colleague said the congregation is trying to rebuild while honoring the victims. Their tone of voice suggested that the events of October 2018 continue to rest at the forefront of many Pittsburghers’ memories.

During my commute that summer, the people on the street and in their cars continued about their normal days, hustling by a building with such a tragic history. But, a picture of what diversity, community relationships, and city dynamics might look like in Pittsburgh slowly emerged for me. And as I passed by this building, I wondered what my interviewees would think of this story… if they thought of this story.

-Charlie Williams

For refugees moving into this landscape, there is a lot of history to pick up on, much of which migrants will not understand without intentional study and English competency. Being in a new city, let alone a new culture with a different language, is overwhelming for anyone. Yet, stories like those from East Liberty or Tree of Life knit together to make up Pittsburgh’s complex social fabric which refugees must grapple with during their integration. Whether or not refugees in Pittsburgh ever step foot into Squirrel Hill or pass by the Tree of Life, the history of race in Pittsburgh will continue to impact newcomers' lives in overt and covert ways.

BOX 3: The Refugee and Host Community Relationship: A Practitioner’s Perspective

One of our key informants at Hello Neighbor, Abby Jo Perez, shares her perspective on the relationship between refugees in Pittsburgh and host communities.

Throughout my career as a resettlement practitioner, across three different cities, I worked with refugee communities from over 18 countries who speak dozens of different languages and hold many identities (racially, ethnically, religiously, linguistically, socio-economically, etc…). Racism and xenophobia are not new concepts, but when refugees arrive in the US, they’re faced with the nuances and complex histories of the country and the cities they move to, like Pittsburgh. While resettling, refugees add to their various identities and see those identities evolve. Being in the US comes with opportunities to self-proclaim new identities but also to face extrinsic labels placed on them by American society as they navigate new communities, schools, and jobs.

A critical component of the resettlement journey provided both internationally and by resettlement agencies is a core service called Cultural Orientation (CO). CO covers 15 topics about life in the US, including cultural adjustment. As a resettlement provider, everything we do with clients can be made a point or lesson under the umbrella of cultural orientation. This can often include discussions on racial or ethnic differences, current events, and US history. Often time to have conversations on these topics with refugees is limited while also providing appropriate language access. Even in the event of having either a shared fluent language or interpreter, the complexity of unpacking racial comments in a mindful, trauma-informed manner can be inappropriate. In understanding how refugees are conscious of and navigate race, one should consider the questions refugees ask organically during their resettlement periods. Throughout my career, I have had many direct opportunities to pull anecdotes from talking with my clients about these questions. When race and ethnicity in the US become focal points of conversion, there is a level of nuance and complexity missing from the resettlement world’s understanding. It is the resettlement field’s responsibility to prepare new arrivals to step into the realities of US systems, including realities of US racial and social norms. There may not be ways to fully prepare people for what they face, but deeper intentionality and understanding can help to cover gaps in explaining race and ethnicity as they are understood in the US.

Here are some situations in which racially-based questions have been posed to me by refugees. The first story, in particular, comes to the forefront of this conversation. In downtown Pittsburgh, I was taking a group of young, single, African men to enroll in an English class. At the time, the trial for the shooting of Antwon Rose, a teenage Black boy killed by police, was happening. There was a sharp upward tick in police presence in the city during the trial. As we made our way through the city, seeing several police officers on horses, bicycles, patrol cars, and walking officers, the men became very excited. They asked about the police and before I could figure out the best way to explain the situation, one of the men said how “good it is to see police being nice.” They followed with stories of corruption, police with machine guns, and a heavy distrust for police due to their brutality in the country they came from. They described a sense of comfort in seeing police on their horses and seemingly approachable. On the flip side, the police presence was due specifically to the fact that police officers were on trial for a racially-based fatal shooting of a Black teenager.

My feelings were hard to wrangle. I checked in with myself and acknowledged the anger and distrust in policing that I was experiencing. I felt protective and limited in my role as a case manager. I didn’t want to say the truth about the situation as I saw it. Yes, the police are behaving much more peacefully than my clients’ description of police in their home countries, but the reality is that as Black men, their interactions with police are likely to be different. Add in their language limitations and again, the interactions will be different. I didn’t want to take the hope away from my clients but I also felt deeply protective and eager to prepare them adequately for the realities they may face in the future.

Another story to contextualize the nuanced intersectionality of race and ethnicity comes from two comments made by a young, middle school refugee girl and an elderly refugee individual. Different refugee communities and local US-born residents attended a community after-school program together. Racialized comments were thrown at new arrivals from other refugees and US-born folks. The situation peaked with a physical altercation between youths, leading to a town hall event across communities to address the situation. The young girl’s comment following the fight she witnessed was, “we thought we would have white people be mean to us because we’re different but we didn’t expect Black Americans or other refugees to be mean, too.” At a town hall by the resettlement agency which had resettled several families in the immediate area (including the young girl and her family), the agency aimed to be neutral and approach the differences across a variety of intersectional angles. There, an elderly woman raised her hand and said, “this [situation] is about racism, it’s racism and we need to just say that it is about racism.” These two comments in particular point to the importance of comprehensive conversations with refugees across generations and throughout all refugee communities. There is a need for additional research to understand how to best tackle the education of US social norms, intersectionality amongst refugee ethnicities, and how to handle the diverse understandings of race globally and domestically. The US-born participants expressed similar sentiments but ultimately tension remained between new-to-the-country neighbors and US-born neighbors. There was no answer or result of note that changed the landscape. However, the conversations did continue, and clients expressed a desire for more information on the social and political landscape of the US.

Again, as a white woman who is a resettlement practitioner, being told that my clients expected racism from me is not surprising. These conversations and others I’ve experienced illuminate the very real reality that America is a refuge but is in no way perfect. This is not new for resettlement practitioners - we all know that moving to the US is a trauma in itself and the period of cultural adjustment can be very difficult. It’s easy to see the benefits of moving to the US for a new, safer, life but it’s critical to acknowledge that the new life is not one of ease. In fully and consistently acknowledging this, the resettlement world can continue to question itself to continually evolve in inclusivity and magnification of the welcoming impact.

-Abby Jo Perez

Analysis

Refugees’ Perceptions of Pittsburgh

The refugees we talked to in Pittsburgh had positive feelings towards the city and the US generally. Many refugees viewed the US as a place of respite compared to their countries of origin. This sense of sanctuary combined with statements that evoked the “American Dream” - a view of the United States where freedom, equality, and economic opportunity are available to anyone who can make a home there.

When we asked our participants about what they thought upon arriving in Pittsburgh, everyone’s faces immediately lit up. One participant, a boisterous Congolese man, exuded an undeniable joy in his responses. Describing what it felt like to step off the plane his first day, the man energetically said “I’m free! I live!” For another more soft-spoken participant, resettlement in Pittsburgh finally meant moving from survival to stability.

“We never live [in Afghanistan]. It’s only survival…. Like I just had a birthday… I could say like I lived (emphasis added) maybe a couple years.”

- Afghan man

The release that these participants expressed aligns with the general refugee population’s views of the US. The IRC reports that for the refugee population and multi-level organizations that serve them, “The US resettlement program is regarded as the world’s most successful and secure… It’s an enormously selective program with multiple layers of security checks.”

Diving deeper into how our participants gauged their sense of belonging to US communities, we asked several questions about building relationships with US-born individuals in Pittsburgh. For nearly all participants, US-born Pittsburghers were viewed as welcoming and friendly. This observation remained even if refugees simultaneously reported other experiences of discrimination or racial profiling.

“They are very kind, very kind and very friendly… American people are very open.”

- Afghan woman

Refugee perceptions of their own co-nationals in the US, in contrast, took on a slightly more unfavorable tone for some. Belonging in this sense was a more complex concept that balanced appreciation for one’s cultural identity and frustration when intergroup tensions flared. As one young Afghan woman reflected:

“The city is one of the best cities. I love Pittsburgh a lot,” but… “I just want to go somewhere where there is no Afghan families.”

- Afghan woman

The unease of this young woman illustrates that after resettlement refugees search for ways to build communities of belonging. Moving could be one answer. A study by the Stanford Immigration Policy Lab, found that 17% of the nearly 450,000 refugees who resettled in the US between 2000 and 2014 moved to a different state after one year. Moves were instigated by a need for “better job markets and helpful social networks of others from their home country.” However, our participants continued to articulate a desire to remain in Pittsburgh, referring to the city as home.

In our position as researchers, it is possible that despite our introductions, refugees associated us with a resettlement agency (Hello Neighbor) and expressed positive attitudes out of a sense of duty to the organization that helped them. Additionally, since this study did not use interpretation, it may have been difficult for refugees to express their complex levels of relief, fears, and frustrations. One key informant said that participants' statements may be “reflective of where clients are in their resettlement journeys” and that “resettlement is a roller coaster” where clients' happiness peaks and wanes over time. It would be beneficial for practitioners in Pittsburgh to continue exploring these feelings in the future.

Navigating Race Relations in Pittsburgh

As we dove deeper into racialized experiences, refugees shared a variety of ways about how they learned what race means in the United States and how race affected their feelings of belonging.

For this case study, we borrow from the “spaces of encounters” framework described by Helga Leitner in her 2011 study about the politics of belonging in small-town America. In Leitner’s description “spaces of encounters” are “encounters with difference” that challenge a refugee and/or host’s “cultural and racial boundaries, boundaries of place, and entitlements to economic and political resources.” While racialization and othering are twisted into this process, being open to change creates possibilities to negotiate across perceived differences and develop a new understanding of place and belonging. In addition to this concept, we also utilize the domains of integration framework to analyze our participants' responses. These are areas that are significant markers of refugee integration into society and are commonly understood to include economic, social and communal, linguistic, or housing domains among others. From these two frameworks, we understand school, employment, social media, and community encounters (not tied to specific locations) as the primary locations where refugees in Pittsburgh learn about and experience racism.

School

Schools are where refugees encounter their host communities’ culture and citizens. Several participants said they experienced racism in the classroom. One Afghan woman said that when she attended high school in the US, some of her classmates were mean to her, saying “bad words” to her in English.

“She [classmate] used to be very mean. She was OK with other kids. Only me, my sister, and two other Afghan kids. She was saying bad word in English.”

-Afghan woman

School is not only a place to experience racism. Through school curricula and interactions with other students, refugees learn about race relations in the US. An Afghan man told us that he learned about racism in the US through his coursework at university. A Congolese man also mentioned a history class where he studied how Black people were treated in the 1990s. He also shared about learning the significance of racial categories in the US from a school friend:

“I was asking my school friends, ‘why are they talking about race? They look the same?’ And they said ‘No, you can call him white, but you can’t call him white ... because they are not from the same country ... he from the US, but he is Asian, he’s an Arab guy."

-Congolese man

Employment

Employment and work are also locations of refugee learning. Economic integration was a concern for our participants, and employability eclipsed perceived racial identity as a priority in their lives or point of anxiety. For example, certificate recognition (for a medical degree or teaching credential) surfaced as an area of stress. Across the US, foreign professionals of any immigration status must face a patchwork of state and organizational policies determining their recertification. Paired with a complicated, expensive system and the discounting of overseas experience, foreign professionals' ability to enter the US workforce is limited.

The workplace served as a “space of encounter” where refugees learned about race in the US, and in one case, the effects of certification and discrimination coalesce. A woman who formerly worked as a science professor in Afghanistan reflected on her lack of US credentials and the advice she got from her case manager about anti-Asian racism at a local university:

"One day I thought if my English was good I would...be a teacher at university… My friends told me ‘You’re good because… your pronunciation is very clear…’ But the head of the agency… told me ‘I give you advice, please don't go to [the] university because… students mostly don't like Asian people and they will give you very low number and then they will fire you and you will be very in bad mental condition.’”

-Afghan woman

Social Media

For a few of our refugee participants, social media was where they engaged with US depictions of race relations. Facebook and Tik Tok are places where community is created and identity is shaped. Online encounters, paired with in-person ones, contribute to how refugees form perceptions of their new homes based on who they “like”, follow, and the posts they click on. In Pittsburgh, the refugees who mentioned social media were in their twenties. In their descriptions, videos depicting racism and discrimination were not searched for but appeared on their feeds. However, once they viewed these posts, our participants connected patterns to build understanding. In describing her observations of posts about police violence at traffic stops, one Rwandan participant said:

"From this observation here, you can learn about what is happening… then from that, finding a way to make sure something doesn't happen to you… What would I have done? If I was in that situation to get myself out of that… put your hand out the pockets so that they can see or your hand on the dashboard… watching all these stories and reading, let's find a way to avoid that same thing happening to me.”

-Rwandan woman

In an unfortunate development, the Hello Neighbor Instagram account reported one of its clients was the target of hate by a Pittsburgh resident. In the November post, a picture of a new neighbor’s door defaced with hate speech read: “Some are welcome, some are not. You are not! We’ll be back, leave.” Hello Neighbor used the post as an opportunity to reinforce its mission to support refugees and reiterate that hate is not welcome in their community. Future posts by Hello Neighbor and other agencies working in the city might contribute to the social media landscape to promote the importance of belonging and how refugees learn about their US communities.

Community Groups: Encounters with US-Citizens and Co-Nationals

Everyday social interactions influence refugees’ perceptions of race and their positions within society. Refugees encounter racial interactions on buses, at grocery stores, and in many other public spaces. Some refugees encountered verbal assaults while others used observation to make meaning of race and racism. During our interviews, one Afghan man shared his experience of being yelled at angrily with words such as Al Qaeda, Osama bin Laden, and Allahu Akbar, while playing soccer. Even though the Afghan man recognized the inaccuracy of these statements (bin Laden was Saudi-born), the demeaning phrases enabled the Afghan man to begin understanding how US race relations are applied to other individuals.

An Afghan woman also mentioned that she learnt about racial differences in the US on a bus ride in Pittsburgh. On one ride she observed tensions between a Black patron and a White bus driver. The patron was perceived by the woman as aggressive and yelled at the driver to open the door. The woman said she was scared by interactions like these and had to calm herself when encountering similar situations.

Limits to Refugee Understanding and Learning About Race

While refugees experience and learn about US race relations in spaces of encounter and domains of integration, refugees face some limitations in developing their understanding. Many refugees we interviewed mentioned that their limited English abilities hinder their understanding of US race relations. They found it difficult to differentiate race and ethnicity in the US, particularly because race does not carry the same importance in their home countries, where in some instances, ethnicity matters more.

English Ability

In our interviews, younger participants with higher English skills were more likely to report their experience of racism in Pittsburgh compared to older individuals with limited proficiencies. One possible reason is that even when their English abilities are limited, younger refugees interact more frequently with US-born people at work or school compared to older refugees. At work or school, English proficiency develops rapidly and refugees better understand situations when they encounter or witness discrimination. For instance, an Afghan woman said she initially had a hard time interacting with and understanding her classmates at school due to limited English skills. However, as her English improved, she discovered that one of her classmates was racist towards her in their interactions.

Older refugees can learn about US racism even when they remain in their houses, by viewing TV news stories about racism, but their difficulties understanding English limits their comprehension skills. For example, a son of an older Congolese participant mentioned that while his father saw the Black Lives Matter movements on the news, he could not understand what it was because it was in English. The father instead had to rely on visual cues. This is another indication of the importance of social interaction in host communities to learn about construction of race.

Race and Ethnicity: Definitional Variations

Many participants found it difficult to distinguish the difference between “race” and “ethnicity,” using the terms interchangeably. For those with advanced levels of English, it wasn’t until our team defined ethnicity as “a social group defined by similar language and culture” that participants described observations in their host countries related to ethnicity. Refugees in Pittsburgh learn about the US definition of race and its categorization in schools, workplaces, media, and through interactions with the local population.

“I was asking, ‘why they talking about that [different races]? They look the same?’ And they [classmates] say ‘no, you can call him White, but you can't call him White.’ And I was like ‘why?’ ‘Because they are not from the same country.’ And I was like, ‘where did he come from, the White guy?’ And they were like ‘he from here. But he is from Asia…’”

– Congolese man

Afghan refugees said that they thought more about race when they filled out forms for the US government bureaucracy. They identified themselves as Asian or White but were unsure of their “official” race according to US categorization. Some Afghan refugees mentioned that they did not understand why these categorizations existed in the first place.

“I’m always confused about that. Since Afghanistan is located in the center of Asia I always tick Asia.... (B)ut most of our friends thought Asian is belonging to Chinese, Japanese, Korean and North Korean people... I always write Asian, other people write White.”

– Afghan man

Carrying Over Conceptions of Race

Refugees also demonstrated conceptions of race that carried over from their countries of origin. These focused on perceptions of their fellow co-nationals, such as stereotypes or prejudice held by Afghans towards Afghans of different ethnicity. Even as refugees navigate a new racial hierarchy in US society, their own in-group racial structures, definitions, and stereotypes still hold meaning and impact refugee integration. Several participants from Afghanistan shared their experiences and were outspoken about discrimination and racism in their home country. Some Afghan participants even framed the fall of the Afghan Government in 2021 as a consequence of long-standing tension among ethnic and racial groups.

Some Afghan participants pointed out that the tension in Afghanistan is carried over to the US in Afghan communities. For example, an Afghan man expressed his frustration to some Afghan refugees in his community who tend to be discriminatory and racist against other resettled Afghans with different ethnic backgrounds.

“Here also they are practicing racism with each other. People from the different ethnicity ... they are just supporting their people. Like if I'm new here and I need help, everyone should help me, that everyone should say that I'm Afghan.”

-Afghan Man

While it was mostly Afghans who described this phenomenon, it’s likely this is a common issue in refugee communities. Our participants – regardless of their countries of origin – said ethnicity carries great significance in their home countries.

BOX 4: Hazara Refugees and Racism Carried Over from Afghanistan

We interviewed several Hazara refugees and found that they face not only racism in US society but also discrimination within their own Afghan community.

Afghanistan is known for its ethnic diversity and is home to over 15 major ethnic groups. One group is the Hazaras, who have been victims of discrimination for decades due to their culture, religion, and physical differences. Several Hazara participants said this discrimination did not end once they were resettled in the United States, and that their needs are sometimes not met due to lack of representation in US social service agencies and lack of US awareness of their unique circumstances. For instance, a humanitarian organization can unintentionally ignore the specific needs of Hazaras since the organization often assigns Afghan workers who are from different ethnic groups, such as Pashtuns, to support Hazaras. These Afghan representatives might not understand what Hazaras need and the ethnic dynamics in their homeland can affect the relationship between Hazaras and other Afghans in the US. The interviewees emphasized the importance of ethnic representation in organizations when supporting the populations that are historically oppressed in their home countries.

“They [Pashtuns] try to interpret our needs to others [Americans usually], so this is the problem… The government and humanitarian agents should convince agencies to recruit more Hazara people… because our situation is different. Our needs are different. Our problems are unique, and we have to talk about our problems.”

- Afghan (Hazara) refugee

Conclusion

Our 24 participants revealed that while many like to live in Pittsburgh, those with higher English proficiencies are more acutely aware of racism and discrimination. Since racial categorization is context specific, many participants confused race with ethnicity and found it difficult to navigate race relations in the US. Refugees often brought their conceptions of race from their countries of origin, and these conceptions sometimes persisted. In learning about US race relations, refugees identified schools, work, social media, and community conversations as spaces where they were confronted with experiences that re-framed and challenged their worldview and created new conception of identity.

Pittsburgh is a dynamic city that over the years has helped refugees resettle and restart their lives. However, organizations in Pittsburgh can serve their new neighbors more effectively, by confronting the history of race and immigration in their city. In doing so, Pittsburgh can engage with its community members more deeply, host and refugee alike, to truly encourage belonging and advocate for equity.

As a final note, we want to stress that this study was exploratory, and only involved conversations with a small number of refugees and Hello Neighbor key informants. Further research will promote our understanding of refugee perspectives on diversity, in the pursuit of a more just resettlement system. During our study, we identified several limitations and challenges related to exploring the sensitive topic of race. These included our lack of the ability to speak our participants’ home language, and how our identities as interviewers affected the research. We discuss these and other limitations further in Appendix A and urge researchers to take them into account in future research

About the Authors

Yumeka Kawahara

YUMEKA KAWAHARA (she/her) is a second-year MALD studying Human Security and International Organizations. Her main academic focus is refugee integration processes and the role of civil society. She is from Japan and earned LLB at Kyoto University with 1-year study abroad experience at Sciences Po Paris. She worked with several think tanks and non-profit organizations in the US, Japan, France, Singapore, and Cameroon to tackle international affairs including migration issues.

Charlie Williams

CHARLIE WILLIAMS (she/her) is a second-year MALD student at Fletcher, focusing on gender analysis and international organizations. Prior to Fletcher, Charlie received her BA in history from Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo and worked with a food security non-profit in Senegal. She is passionate about community engagement and advocacy, and through her studies hopes to work in resettlement post Fletcher.

Abby Jo Perez

ABBY JO PEREZ (she/her) is an Intensive Support Program Manager at Hello Neighbor. She holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Interdisciplinary Studies with an Emphasis on Human Awareness from Bay Path University. She has almost 10 years of experience as a resettlement practitioner. She is passionate about reproductive justice, cultural humility, and linguistic justice. Additionally, she is a trained birth doula and a Perinatal Health Equity Champion.

Sohrab Saljooki

SOHRAB SALJOOKI (he/him) is a history and philosophy student at Carnegie Mellon University. He has studied, lived, and worked in Pittsburgh since 2019. He is the son of an Afghan refugee and immigrant.

References

References

1. Barone, A. (2022, November 4). What is the American Dream? examples and how to measure it. Investopedia. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

2. Bell, J. (2019). The Resistance & the Stubborn but Unsurprising Persistence of Hate and Extremism in the United States. Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, 26(1), 305–316.

3. Bentley, F. (2020). Migrants and Refugees Experience American Racism. The Pulitzer Center. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

4. Biedka, C. (2019, February 18). Black migration making great impact on Pittsburgh region. TribLIVE.com. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

5. Bubar, J. (n.d.). The Jim Crow North. The New York Times Upfront. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

6. Chavez, N., Grinberg, E., & McLaughlin, E. C. (2018, October 31). Pittsburgh synagogue gunman said he wanted all jews to die, criminal complaint says. CNN. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

7. CMU History. (2018, October 14). Pittsburgh: A Short History. [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

8. Department of Human Services. (2022). Facts and Statistics. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

9. Gessen, M. (2018 October 27). Why the Tree of Life Shooter Was Fixated on the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. The New Yorker. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

10. Handayani, F. S. (2016). Racial Discrimination towards the Hazaras as reflected in Khaled Hosseini’s The Kite Runner. LANTERN (Journal on English Language, Culture and Literature) 5, (4).

11. Hello Neighbor [@helloneighborhq]. (2022 November 10). Here at Hello Neighbor, we instill a refugee-first mindset into everything we do. [Instagram post]. Instagram.

12. Hasrat, M. H. (2019). OVER A CENTURY OF PERSECUTION: MASSIVE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION AGAINST HAZARAS IN AFGHANISTAN. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

13. Hassan, A. (2019, March 22). Antwon Rose Shooting: White Police Officer Acquitted in Death of Black Teenager. The New York Times.

14. Heinz History Center. (2022, October 14). Fort Pitt Museum. Retrieved August 18, 2022.

15. Howell, J., Goodkind, S., Jacobs, L. A., Branson, D., & Miller, L. (2019). Pittsburgh's Inequality Across Gender and Race. City of Pittsburgh's Gender Equity Commission. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

16. International Rescue Committee. (2017). Coming to America: the reality of resettlement. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

17. Immigrant Services & Connections. (n.d.). Welcome to ISAC. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

18. Jacobsen, K.& Simpson, C. (n.d.) Defining Key Terms: Integration. Feinstein International Center.

19. Krauss, M. J. (2020). Land and Power [Audio podcast]. NPR.

20. Lamb, M. E. (2021). City of Pittsburgh, Annual Comprehensive Financial Report: Year Ended December 31, 2021. (10). City of Pittsburgh. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

21. Leitner, H. (2012). Spaces of Encounters: Immigration, Race, Class, and the Politics of Belonging in Small-Town America. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 102(4): 828–846.

22. McCarthy, M. (2021). Welcoming Pittsburgh Annual Report 2021. City of Pittsburgh. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

23. Migration Policy Institute. (n.d.). U.S. Annual Refugee Resettlement Ceilings and Number of Refugees Admitted, 1980-Present. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

24. Mossaad, N., Ferwerda, J., Weinstein, J., & Heinmueller, J. (2020). Why do refugees move after arrival? opportunity and community. Immigration Policy Lab. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

25. New American Economy. (2022). Immigrants and the Economy in: Pittsburgh Metro Area. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

26. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. (2014, May 19). Earlier immigrants reshaped the region, then blended in (2014, May 19). Retrieved November 7, 2022.

27. Rabben, L. (2013 May). Credential Recognition in the United States for Foreign Professionals. Migration Policy Institute.

28. Reyn, I. (2021, October 27). What happened after the most deadly antisemitic attack in American history? The New York Times. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

29. Rutan, D. (2021, November 5). How housing policy over the last century has made Pittsburgh what it is today. PublicSource. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

30. Southern Poverty Law Center. (2022, November 4). In 2021, 30 Hate Groups Were Tracked in Pennsylvania. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

31. Thomas, S.W. (2020). Enduring Slavery: Resistance, Public Memory, and Transatlantic Archives. Early American Literature, 55(2), 588–592.

32. Tree of Life Congregation. (n.d.). About Us. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

33. UNHCR. (n.d.). What is a Refugee? Retrieved November 7, 2022.

34. United States Census Bureau. (2021). QuickFacts Pittsburgh city, Pennsylvania. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

35. Visit Pittsburgh. (2017, August 31). Pittsburgh named most Livable City in continental United States. Retrieved November 7, 2022.

36. Visit Pittsburgh. (2022). Explore Our City: Neighborhoods. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

37. Walther, Rayes, D., Amann, J., Flick, U., Ta, T. M. T., Hahn, E., & Bajbouj, M. (2021). Mental Health and Integration: A Qualitative Study on the Struggles of Recently Arrived Refugees in Germany. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 576481–576481.

38. Welcoming America. (n.d.). Welcoming Network Directory. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

39. Williams, C. (personal communication, June 2022)

Appendix A: Limitations

Sample Bias

In Pittsburgh, researchers recruited participants largely through the Hello Neighbor client networks and through other community-based organizations. These pre-existing relationships might have meant that participants were hesitant to express some views because of the researchers’ affiliations with the organizations.

Our samples consisted mostly of Afghan and Congolese resettled refugees. Thus, our study results are much less indicative of other refugee groups, such as Burmese or Ukrainians. We interviewed both new arrivals and refugees who’d been resettled for a long time. The length of their stay in the US ranged from 5 months to 7 years, and the average length is 2.7 years. It is possible that long-stayers have forgotten about their initial experiences on arrival, while more recent arrivals have had less time to formulate thoughts about and experience regarding racial dynamics.

Our study’s focus on racialized experiences could have meant that some participants were more or less likely to participate. For example, refugees with negative experiences might have wanted to talk about these experiences. Others might’ve declined to participate based on concerns about speaking on the topic. As with all research, those with more outgoing, talkative personalities might have been more likely to engage with the researchers and invite the researchers into their homes. Results cannot be generalized to broader refugee populations, either in our case study or the wider US.

Race as a Sensitive Topic

Few people want to acknowledge their own racial biases or express them freely. Participants might speak guardedly in interviews or play down their own actions and thoughts. In Pittsburgh, one participant said that refugees are “scared about talking about [race]” to outsiders. The researchers assured interviewees that all answers were confidential and scrubbed of identifiers.

English Language

We did not use formal interpreters in this study. Though we sometimes used Google Translate to communicate specific phrases, the lack of interpretation assistance meant the study’s sample is limited to refugees who could speak English. In some cases, when we talked to families, a family member provided impromptu interpretation, but for the most part, those with little English might not have fully understood our questions. The RiT Project has historically avoided the need for interpreters by training refugee researchers or others from the community who speak the language. However, given timeframe restrictions, organizational capacity, and specific IRB clearance, the RIT project was unable to provide or train interpreters for this study.

The “Interviewer Effect”

The interviewer’s age, gender, and level of experience alter the ways in which participants engage in a study. Our researchers were all women in their mid-twenties: two were U.S. born and White and one was Japanese/East Asian. Our identities might have altered our participants’ responses. Men and women could have replied differently, reflective of the researchers’ gender, or participants might have been hesitant to reflect their true feelings about White or Asian groups within the United States.

Appendix B: Refugees in the United States

The United States has a long history of welcoming refugees, and though recent resettlement numbers have declined, the United States remains one of the top resettlement countries in the world. More than 3.5 million refugees have been resettled in the U.S.[38] Resettlement of refugees is conducted through the United States Refugee Admission Program (USRAP). The program is composed of several federal agencies, including the State Department, Homeland Security, Department of Justice, and the Department of Health and Human Services.[39] The President of the United States each year determines the number of refugees who may be admitted, along with the designated nationalities and processing priorities.[40]

The United States' history with refugee settlement dates back to the end of World War II, when The Displaced Persons Act of 1948 (or the first specific "refugee" statute enacted by Congress), intended to assist the nearly 7 million displaced persons in Europe as a result of World War II.[41] Though the United States did not sign the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees established by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), it continued resettling refugees during the Cold War period through ad hoc resettlement initiatives focused on taking in refugees from Communist States.[42] Following the large-scale resettlement of over 300,000 Southeast Asian refugees in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as becoming a signatory to the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, Congress passed the Refugee Act of 1980.[43] The Act established the U.S. Refugee Admission Program, adopted the U.N. definition of a refugee, raised the number of refugees permitted into the US, and created the Office of Refugee Resettlement to manage resettlement operations. According to the Act, the President, in collaboration with Congress, determines the annual number of refugee admissions and how these admissions are distributed among refugees from various parts of the world. As a result, refugee resettlement in the United States is dependent on the country's present political climate, or zeitgeist, as well as the political party in power. Since the 1980s, refugee resettlement demographics in the U.S. have become more diverse and less defined by Cold War dynamics, with refugees coming mostly from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Syria, Burma, Iraq, Somalia, and Bhutan.

A large shift in resettlement patterns occurred after September 11, 2001, when refugee resettlement numbers plummeted amidst security concerns, reaching a low of 27,110 in 2002. Numbers under the Obama administration steadily began to increase (with yearly resettlement numbers ranging from 56,424 – 84,994 between 2008-2016), only to be decimated under the Trump Administration.[44] Trump, who claimed that "refugees constituted a national security, economic, and cultural threat to the country,” [45] reduced refugee caps to record lows and instituted policies limiting those who qualify for resettlement and enabling state governments to prevent refugee resettlement in their domains. The Trump Administration temporarily suspended admissions of refugees from 11 "high-risk" countries and later imposed further screening. Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Mali, North Korea, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen "accounted for 43 percent of all refugee admissions in FY 2017, but dropped to 3 percent in FY 2018, before climbing to 6 percent in FY 2019 and 14 percent in FY 2020."[46] Trump's policies had significant long-term consequences. For example, a lack of federal funds forced resettlement agencies and local non-governmental organizations that support refugees to shut down offices and lay off workers.[47] This, combined with the year-long suspension in refugee resettlement in the United States due to the COVID-19 pandemic, resulted in little over 11,000 refugees being resettled in the United States in 2020.[48]

Under the Biden Administration, the annual refugee cap increased substantially from the previous administration, jumping to 125,000 in 2022.[49] However in the fiscal year 2022, just 25,465 refugees were resettled, falling 80% short of the target.[50] Not included in these numbers, though, are the nearly 90,000 Afghans and 60,000 Ukrainians who entered the country as humanitarian parolees as a result of conflicts in those regions.[51],[52] Advocates have sounded the alarm about the low refugee admissions, citing an unparalleled global displacement issue--over 100 million persons displaced in 2022--aggravated by war, ethnic conflict, oppressive regimes, and natural disasters. According to the UNHCR, more than 2 million refugees are in need of resettlement in 2023, a number that increased 36% as compared to 2022.[53] In 2023, the Biden Administration again set the refugee admission ceiling to 125,000 refugees and took additional steps to resettle this number. These steps included deploying approximately 600 additional personnel at U.S. refugee processing centers overseas, increasing the number of local domestic resettlement offices from 199 to 270, and expediting refugee processing.[54] As refugee agencies continue to rebuild, legislators, refugee activists, practitioners, and researchers alike continue to seek legislation to secure financing and human-centered resettlement policies in the U.S.