Learning to Integrate

INTRODUCTION

Six years ago, I was living on the historic Voortrekker Road in Parow, Cape Town, sharing a house with three brothers from the Democratic Republic of Congo. My next-door neighbors were immigrants from Kenya and Rwanda, and my Rwandan neighbor’s two daughters were in Grades 8 and 9 at Maitland High School. Their mother was working at a family restaurant in Plattekloof, and she often asked me to help the girls with their homework. I noticed they were really doing well in Mathematics, but were struggling in subjects like History, Geography, and English. The elder one said she was not getting the help she needed from teachers and she struggled to cope. It seemed she was likely to repeat Grade 9 in the coming year. She had one close friend, a classmate from Kenya. The two siblings had less time to do their schoolwork when they started to help their mother at her work place. Their mother’s income was not enough for rent, school fees, and to support the two younger siblings. A year later, the family was featured in a local paper, appealing for aid as the two siblings had been kicked out of school due to outstanding fees.

Two of the three brothers I was staying with had enrolled in different high schools. One said his teacher for English language explained concepts in Afrikaans, a language he did not understand. He attended class with little help or motivation. He had no friends in the school. At the second brother’s school the teachers were very helpful, and he even had a few South African friends with whom he would spend weekends. Despite their difficulties, both brothers passed their matric exams and completed Bachelor of Technology degrees at the Cape Peninsular University of Technology. They are now working in the city.

Listen to a conversation with the author.

My experience with these families led me to focus this research project on the integration of first-generation immigrant students in Cape Town. I wanted to find out if conditions were still the same or have improved or worsened. I was also interested in the reasons for successful integration: were the brothers’ different experiences more about their demeanors or about their schools? In this research, I am mainly interested in students’ experience and how much schools are helping them integrate into South African society. This report documents some of this experience and makes suggestions about how first-generation students can be helped.

LOCATION

Continue to the appendices for more information on the methods used for this report, and for background on refugees in Cape Town and South Africa.

THE URBAN IMPACT

CHALLENGES INTEGRATING TO EDUCATION SYSTEMS

In South Africa there are academic, economic, and psychological challenges facing African refugee students that adversely affect their ability to integrate and cope well in school (Kanu, 2008). The challenges include language, foreign students’ ability to establish friendships with their South African counterparts, changes in curriculum, the extent to which the educational environment was discriminatory (e.g. not being addressed by derogatory names by colleagues and teachers), equality of resource accessibility, and freedom to share cultural differences in a friendly and inclusive school environment that embraces diversity. These challenges can be overcome through support programs within the school and in the broader community.

The 15-19 year-old students in this study arrived in South Africa after completing their primary education in their respective countries (Angola, DR Congo, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda, Swaziland, and Zimbabwe). They were raised and educated in environments quite different from South Africa. For most of them, Cape Town was their first experience of a multicultural and multiracial society, as they come from societies that are almost entirely ethnically homogenous.

The primary challenges faced by these first- generation immigrant children include being economically disadvantaged, facing hostile host communities, and language barriers: those from DR Congo and Congo Brazzaville (part of Francophone Africa) speak French, and the ones from Mozambique and Angola (Lusophone Africa) speak Portuguese. Additionally, first-generation immigrant children have difficulties obtaining the permits and paperwork to enroll and stay in schools. Further, their schoolmates are prejudiced against them.

The sociological literature recognizes schools as the secondary agent of socialization, after the family. Many immigrant students experience disruption of the curriculum as the South African system of education is different from that in other former English and French colonies in Africa. As such, the school—including both teachers and fellow students—has a crucial role to play in the integration of young immigrants, enabling them to become proud members of the school, with equal access to opportunities and resources.

EDUCATION & THE LAW

The Western Cape Education Department’s (WCED) “Admissions Policy for Ordinary Public Schools,” under the subtitle “Admission of non-citizens” clearly states what is required of non-South African students to study in South African schools (Western Cape Government, 2017). However, some officials interpret these laws differently in practice. An example is when students whose parents have asylum permits are asked to produce study permits because the school authorities misinterpret the law. Karabo Ozah, an attorney and Deputy Director of the Centre for Child Law, states that this “is not the correct interpretation of the law,” (Gwala, 2017).

I got interesting responses from students and school authorities when I asked them about the application of these laws. At one high school, the school does not ask for an asylum document or study permit when students enroll. The issue only arises when they write matric exams (final high school exams required for graduation and university entry), for which they need these documents. According to the school principal: “We allow them to learn, but they cannot sit for an exam as they will not be able to get their certificates.” At another high school, the administrative secretary said they admit students as “they have a right to learn,” but the school goes a step further in assisting with a letter to the University of Cape Town Law Clinic or Scalabrini Centre. The law clinic and school assist the students and their parents in applying for documents at the Department of Home Affairs. One school secretary said the WCED fines them R3,000 (approximately USD 250) for every undocumented student they admit, a claim that was strongly refuted by the WCED officials.

REFUGEE EXPERIENCES

LANGUAGES

At the four schools selected for this case study, English is the primary mode of instruction and compulsory for all students. In addition, students are required to learn a second language, either Afrikaans or IsiXhosa. Mastering a local language enables foreign students to communicate at all levels of the society and promotes easier integration into the local community.

More than half of the students I interviewed were comfortable saying a few words in these languages even when their colleagues interjected and laughed, and at times corrected them. It appears they are taking to these languages well. However, the other half were not so keen to demonstrate or “show off.” Some said they are just taking these classes for exam purposes. These students are not so keen on learning a language they will never utilize when they return to their home countries. My own view is that South Africa is a powerful nation with multinational corporations throughout Africa, and making it compulsory for foreign students to learn a local language appears like an attempt at assimilation akin to the French colonial model.

All four schools have a high number of students who speak French, mostly from DRC. Some schools offer no French classes, and those that do, such as Rhodes High, charge extra for French class. Parents appear to be comfortable with that arrangement because they think their children will not stay in South Africa forever and they want to equip them with the language that would make it easier for them back in their home countries.

Although they do not offer French classes, Maitland and Bloubergrant High Schools recommend pupils to established French teachers and tutors outside the school. For this outside instruction, parents foot the bill as agreed with educators. The Principal of Vista High said that the school had no such arrangement for its students or a plan to do so despite having many students who studied in French at the primary level in their home country. The deputy principal of Bloubergrant said it would be good if the schools could let the students drop either IsiXhosa or Afrikaans for French, but the problem lies with enrollment at South African universities, where students are required to have a local language on matriculating from the South African school system.

A group of students from Maitland High School. Photo by author. Click to enlarge.

XENOPHOBIA & INTEGRATION

One of my most interesting discussions was with four students from Zimbabwe. I wanted to find out who their friends at school were, if they ever faced discrimination and if they were ever called derogatory names by their South Africans schoolmates and teachers. These questions induced heated debate. Three of them agreed they had no South African friends, and preferred to hang around on their own. One who spoke IsiXhosa and Afrikaans accused the other three of isolating themselves, and even lying when they claimed they are often called by strange and uncomfortable names.

In another interview with students who are prefects, they told me that students respected each other all the time, and would not say anything negative about their colleagues. It seemed like the prefects felt they had a duty to defend the image of the institution. However, a third of the students I interviewed made it clear they were more comfortable in the company of other foreigners than with South Africans nationals. A small group of Zimbabwean and Congolese students from Vista High included a friend from Saudi Arabia. None said they had experienced being called names.

The Principal of Vista High said cases of xenophobic name-calling do happen, and the school takes such incidents seriously. Students are cautioned and counseled on this type of behavior because sometimes they say these things without attaching meaning to the names. A teacher from Zimbabwe said students at Bloubergstrant respect foreign students because they like and respect the foreign teachers serving in the school, seeing them as role models. The staff at Bloubergrant High School is diverse: 13 are white, and 15 are black, among them are 3 Zimbabweans. One deputy principal said some of the most hardworking and best students and teachers at the school are foreign. Each of the four schools has at least two expatriates among the teaching staff.

SOMALIS IN CAPE TOWN

Whether one is in the center of Cape Town or in the townships, there is bound to be a spaza shop (convenience store) nearby, with a good chance that the shop operator is a Somali. However, while Somalis work in a range of neighborhoods, Somali children are conspicuously absent in all four schools in this study. It could be, as one researcher says, that “Many Somali parents are not sending their children to South Africa’s public schools because they are intimidated by the official processes required to get their children into school and because of the discrimination foreign pupils frequently experienced there,” (Nkosi, 2011).

To counter the problem, the Somalis founded a school called Bellville Education Centre in the area where the Somali community lives. It was founded by the Somali Association of South Africa, with the help of the Scalabrini Centre (Washinyira, 2014).

The school’s webpage says: “Although the BEC is open to refugees and immigrants from any origin, our current enrollment is comprised entirely of adult Somali refugees,” (Bellville Education Centre, 2017). However, news reports suggest that the school is open to students of all ages. It is possible that stating that the institution is entirely for the adult Somali refugees enables them to “safely” operate without any legal challenges related to the exclusion of other communities, as they would be seen to be operating within the laws of the country.

My attempts to explore whether the school was started as a “safe zone” for Somali children were not successful, however. When I visited the Scalabrini Centre, I was told to put my request in email, which did not get a response. When I phoned Abdikadir Mohamed of the Somali Association of South Africa, he said he was too busy to make an appointment, and that he “would not be able to answer a question about [his] community over the phone.”

REFLECTIONS ON COLLECTIVE IDENTITY

In South Africa, Africa Day is not marked by an official public holiday, as it is in most African countries, and schools do little to acknowledge the day. South Africa is widely viewed by its neighbors as behaving like a nation detached. “South Africa is largely insulated from the rest of the continent.

The rest of Africa, however, is very aware of what’s going on here,” (Louw-Vaudran, 2016). On Africa Day 2001, former president Thabo Mbeki, “blamed the levels of xenophobia on the lack of knowledge about the African continent,” (Mshubeki, 2016).

These sentiments were widely shared after the xenophobic outbreaks in 2008 and 2015, when the rest of Africa reflected on the sacrifices they made in the fight against the apartheid regime. It was argued that South Africa should not tolerate the killing of fellow Africans (Heleta, 2015). Yet the most that is done in all four schools is the celebration of Africa Week at Maitland High School when students showcase arts from their diverse backgrounds. The other three schools just encourage students to wear their national colors on the 25th of May.

The schools generally seem to be helping first-generation immigrants to fit in, and some schools go the extra mile. For example, there was a case of two brothers whose parents were deported for lack of proper documents, and the school negotiated with their landlord to allow them to stay to the end of the year. Another encouraging gesture is that the schools are proud of their alumni that have made it to the top universities in the country. They sometimes bring them back to say a few encouraging words to matriculants and attend award ceremonies. Among them are foreigners.

Maitland High School celebrates Africa Week. Photo by author. Click to enlarge.

CONCLUSION

OBSTACLES & LESSONS

Here are a few suggestions on how to promote refugee and other migrant integration in Cape Town. First, French should be offered in all schools. South Africa has eleven official languages, and one school cannot offer them all—let alone the language of the Khoisan who are the aboriginal communities of this land. But French comes with its own advantages over the local languages in a cosmopolitan metropolitan space like Cape Town. While some argue that the language is “colonial,” and teaching it flies in the face of the decolonization process and agenda, it would be beneficial for South African students as it fosters better understanding and appreciation of other foreign cultures, particularly Francophone Africa, a region providing a huge number of immigrants to South Africa. Such a move would minimize the disruption in the learning process caused by changing countries. Like English, these languages build effective linkages between communities and nations in an age of globalization.

Second, the education department should develop a toolkit to help educators deal with immigrant students. Teachers should have regular workshops where migration issues are discussed. This would help them prepare for the increasing numbers of immigrants in the schools. The teaching and learning processes within these multicultural environments can be very complicated, and a program could help both educators and students understand each other’s experiences and dilemmas. Teachers should also have help from experts working in NGOs. Professional psychologists could be brought in to assist, as some immigrant students come from traumatic environments. The schools should consider employing at least one social worker, who could help counsel students. There are many skilled immigrants who can help as volunteers in these capacities.

A helpful model comes from Maitland High School, which has information sheets of all the organizations that help foreign students in need of assistance. The secretary informed me that they make this information available to all the immigrants in the school. This saves time and helps students and parents make informed decisions in difficult times. All schools should emulate this example.

Third, although all the students I interviewed claimed that they had study permits, refugee statuses and asylum permits, it is not encouraging to hear that the Department of Home Affairs usually issues the asylum documents for a period of either three or six months only. That means at some point in the year, the students have to stay away from school and join the long queues at Home Affairs to renew their documents. At times, the process takes days significantly disrupting the students who must stand in queues instead of focusing on study, work, or fulfilling activities. It would not be surprising if some students never renew permits in time, or give up on the process. These permits should be offered for at least a full calendar year.

Information given to students at Maitland High School to educate of them of their rights. Click to enlarge.

Fourth, it is well reported in the local and national press that South Africa has a chronic shortage of qualified teachers (Phakathi, 2017; Savides, 2017), yet there are many qualified teachers from the region and Africa who have received quality training in their home countries, but work menial jobs in South Africa as they cannot secure the permits that would allow them to teach within the South African education system. Again, the problem lies with the Department of Home Affairs. These teachers are well equipped to help both immigrants and South African students. Providing them with permits and regularizing their stay can only be of mutual benefit.

Further information given to students at Maitland High School to educate of them of their rights. Click to enlarge.

Students would also benefit from a better appreciation of African geopolitics, and schools’ curriculums need to focus more on the role played by South Africa and other countries in Africa. That will go a long way in changing teacher and student attitudes towards immigrants. As Heleta (2015) sums up, “this kind of teaching and engagement can also happen in high schools. South Africa’s government has already suggested that making History a compulsory school subject could help to prevent xenophobia.”

Information on NGOs and other organizations that assist immigrants in Cape Town Schools. Courtesy of Maitland High School. Click to enlarge.

THE FUTURE OF INTEGRATION IN CAPE TOWN?

The inclusion of immigrants in the schools of Cape Town enables South African students to learn from foreigners as much as immigrants are learning from the locals. Students have an opportunity to teach and learn from each other. Two South African girls from Vista High School happily greeted me in Lingala when they saw me talking to students from the DRC (they assumed I was Congolese). This was quite an encouraging sign that students are learning something from each other.

Xenophobic attitudes are held by many frustrated older people who believe foreigners are taking their jobs and committing crimes, but young people at school learning alongside immigrants see that those from other African countries are not so different. They even see some of the immigrant students doing menial jobs in a bid to help their parents. That can only help instill in local children the idea of hard work.

“Research shows that despite barriers, immigrant students often hold high aspirations for themselves. These high aspirations make them more likely to put in greater effort to take advantage of educational opportunities and succeed academically. This is part of a phenomenon known as the immigrant paradox,” (McManus, 2016). My experiences and observations suggest that immigrants in South Africa compare their lives with those of citizens and aspire to do better. One deputy principal said clearly the immigrant students seem to work extra hard.

Foreign students face a range of challenges, from switching to a new curriculum, to differing language of instruction, to xenophobia, to the need to work to help their parents in low-paying jobs. It is easy for them to lose interest in school or even lose hope in life. They need extra motivation to concentrate and do well. The schools in Cape Town provide a platform for them to learn, albeit with challenges. What I encountered in this study left me satisfied that the schools are doing a lot to help the students integrate.

However, there is room for improvement: instructor and migrant student workshops; changes to the learning permit length; more accessible options for strategic language instruction like French; and changes to curriculums to focus more on the region and world rather than exclusively South Africa. With increasing calls for decolonization and transformation within South African education institutions, there is a growing awareness of Africa and appreciation of African neighbors. It is evident that the schools are taking strides to help students integrate, making the future look brighter for immigrants in Cape Town.

Barnabas is a Ph.D. student at Rhodes University, and was previously a Curator and Assistant Researcher at the University of Cape Town's Centre for Curating the Archive. He is a Zimbabwean who moved to Cape Town in November 2008, and has since studied, worked, and lived with fellow migrants from Kenya, Democratic Republic of Congo, Malawi, Somalia, and Rwanda, among other countries of origin. He is interested in the experiences and treatment of migrants by hosts communities and immigration authorities. Barnabas studied at Midlands State University in Zimbabwe, the University of Cape Town, and the University of Stellenbosch.

REFERENCES

Ager A. and Strang, A. (2008). Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework. Journal of Refugee Studies, Volume 21, Issue 2. June 2008: 166-191. Available: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen016

Crush, J. (2017). Op-Ed: Myths and misinformation obstruct path to a better migration environment. Daily Maverick. Available: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2017-08-31-op-ed-myths-and-misinformation- obstruct-path-to-a-better-migration-environment/#.WqAsLeexXIU

Department of Home Affairs. (2017). WHITE PAPER ON INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION FOR SOUTH AFRICA. Available: http://www.dha.gov.za/WhitePaperonInternationalMigration-20170602.pdf

Gwala, X. (2017). What the Law Says about Admission of Immigrant Children in SA Schools. WN News. Available: http://ewn.co.za/2017/03/03/listen-what-the-law-says-about-admission-of-immigrant-children-in- sa-schools

Hanna, H. (2016). How teachers can help migrant students feel more included. The Conversation. Available: https://theconversation.com/how-teachers-can-help-migrant-students-feel-more-included-56760

Heleta, S. (2015). Teaching students about Africa may be one way to stem xenophobia. The Conversation. Available: https://theconversation.com/teaching-students-about-africa-may-be-one-way-to-stem-xenophobia-50083

IRIN. (1999). Deprivation breeds xenophobia. Available: http://www.irinnews.org/news/1999/09/17-1

Kanu, Y. (2008). Educational Needs and Barriers for African Refugee Students in Manitoba. University of Manitoba. Canadian Journal of Education; Toronto Vol.31, Iss. 4. Available: https://search.proquest.com/docview/215372453/fulltextPDF/E4523EEB4123430CPQ/1?accountid=14500

Lemanski, C. (2007). Global cities in the South: deepening social and spatial polarisation in Cape Town. Cities, 24(6), pp.448-461.

Louw-Vaudran, L. (2016). “Is South Africa a continental superpower and/or neo-colonialist? 702. Available: http://www.702.co.za

McManus, M. (2016). Here’s why immigrant students perform poorly. The Conversation. Available: https:// theconversation.com/heres-why-immigrant-students-perform-poorly-52568

Mshubeki, X. (2016). Xenophobia in post-apartheid South Africa: A Theological Reflection.

Mohamed, A. and Saltsman, A. (2017). Searching for “participation” in participatory research with forced migrants. In Conducting Research with Refugees. Boston Consortium for Arab Region Studies. Available: http://www.academia.edu/34118973/Conducting_Research_with_Refugees_Reference_Guide_and_Best_Practices_Methods_Handbook

Nicholson, Z. (2011). Bellville a “safe haven” for Somalis. Cape Times. https://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/western-cape/bellville-a-safe-haven-for-somalis-1067257

PASSOP. (1998). Refugee Act. Available: http://www.passop.co.za/wpcontent/uploads/2012/06/Summary- of-the-1998-Refugee-Act.pdf

Pernegger, L., Godehart, S. (2007). Townships in the South African Geographic Landscape: Physical and Social legacies and challenges. Pretoria.

Phakathi, B. (2017). Lack of qualified teachers scuppers efforts to improve S.A.’s education. Business Live. Available: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/national/education/2017-09-20-lack-of-qualified-teachers-scuppers-efforts-to-improve-quality-of-sas-education/

Ramoroka, V. (2014). The Determination of Refugee Status in South Africa: A Human Rights Perspective. UNISA. Available: http://uir.unisa.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10500/13850/dissertation_ramoroka_v. pdf?sequence=1

Savides, M. (2017). SA schools have 5‚139 teachers who are unqualified or under-qualified. Herald Live. Available: http://www.heraldlive.co.za/news/2017/06/06/sa-schools-5139-teachers-unqualified-qualified/

Thompson, S. K. and L. M. Collins. (2002). “Adaptive sampling in research on risk-related behaviors.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 68(Supplement 1): 57-67.

Trost, J. (1986). “Research Note: Statistically Non-Representative Stratified Sampling: A Sampling Technique for Qualitative Studies.” Qualitative Sociology 9(1): 54-57.

UNHCR. (2016). “Forced Displacement in 2016.” UNHCR official webpage available at http://www.unhcr.org/5943e8a34.pdf Feb 27, 2017.

Washinyira, T. (2014). “Somali community run school to learn English.” GroundUp News. Available: https://www.groundup.org.za/article/somali-community-run-school-learn-english_1492/

Western Cape Government. (2017). Policies. Available: https://www.westerncape.gov.za/documents/policies/A

Whittles, G. (2017). Somali spaza shop owners take up arms. Mail & Guardian. Available: https://mg.co.za/article/2017-09-01-00-somali-spaza-shop-owners-take-up-arms/

APPENDIX A: METHODS

The research is a qualitative enquiry based on semi-structured questions, spatial mapping, and a desk review of existing documents on migrant integration in South Africa. I conducted ethnographic observations and qualitative interviews over four months from September to December 2017. My situation as a Zimbabwean immigrant who has been living in Cape Town for the past nine years, is crucial to this research. It influenced my assumptions and expectations and the nature of the interviews I designed and carried out. Though I tried to be as objective as possible, I am conscious of my biases. This report does not aim to eliminate those biases, but rather to be aware of them and present authentic findings, rather than strictly valid findings (Mohamed & Saltsman, 2017).

After interviewing only two parents, I realized that most of the students were not going to voluntarily avail their parents’ phone numbers. Therefore, in line with adaptive sampling techniques (Thompson & Collins, 2002), I adjusted my line of questioning so that students let me know how often the school authorities get in touch with the parents, as well as checking this against what the authorities claimed to be doing for the parents, and how often.

Cape Town has a few Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) working with refugees in schools and communities. Some have adopted or work with certain schools, mostly in the townships.

Africa Unite, for example, works exclusively with schools in the townships of Gugulethu and “Europe.” In order to include a diversity of experiences, I purposively selected four schools that are not in the townships but have a visible presence of immigrants, rather than going through referrals by the NGOs.

I was surprised by how difficult some administrative secretaries made it for me to meet the principals of the schools. Maybe they thought I would ask uncomfortable questions when they heard that my research focused on immigrants. At one school however, the friendly and welcoming Deputy Principal said to me: “If you are looking for this type of information, you have come to the right school.” I was then surprised by how uncomfortable and somehow confrontational the Principal of that school was — she tried to rush me through the interview. and denied me access to the teachers, saying I could only interview them if they volunteered to talk to me.

Except for two meetings I had with groups of students (one at the McDonald’s eatery in Maitland and the other in the Cape Town Central Library), most of my interviews were at informal places like the train stations or the public taxi and bus stands. Interestingly, it was in these environments that the students divulged more information and were quite relaxed.

I followed a non-representative “snowball” sampling strategy in choosing interviewees (Trost, 1986). I sought to interview at least ten students in each of the four schools. I knew a few of the students, especially the Zimbabweans, and asked them to introduce me to their friends or point me to foreign students they knew. Unsurprisingly, most of the interviewees in this sample were Zimbabweans. I tried to balance the numbers of males and females, and all the students I interviewed fit within a 15-19 years age range. Most matriculants fall within this age cluster.

Of the 40 students I interviewed, 22 have study permits, 10 have asylum documents, and 8 have refugee status. Even though the media says South Africa has many undocumented immigrants, none of my interviewees openly admitted that they are undocumented.

APPENDIX B: REFUGEES IN SOUTH AFRICA

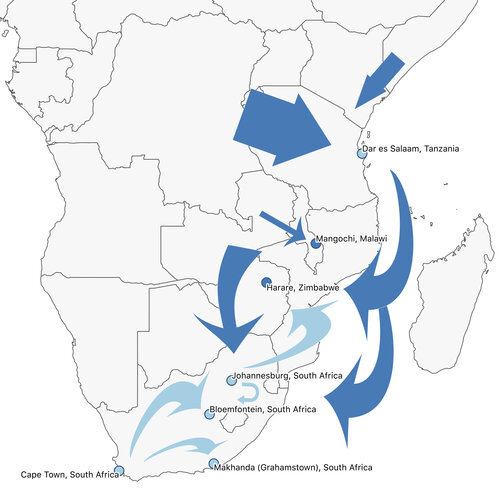

The migration of Africans from neighboring countries to South Africa can be traced back to the discovery of gold and diamonds. People came from as far as Malawi, Kenya, and Zambia to work on the mines of South Africa under the migrant labor system. Numbers of refugees escalated in the 1980s and 1990s because of civil wars in neighboring Mozambique and Angola. Economic and political problems in Zimbabwe post-2000, and the seemingly endless civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo have ensured that people keep trekking down south.

According to UNHCR (2016), South Africa received 35,400 individual asylum claims in 2016 (compared to 149,500 claims in 2009), of which Zimbabweans were the most numerous at 8,000, (a significant drop from the 17,800 Zimbabwean applicants in 2015). In 2016, there were 5,300 applications from Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), 4,800 from Ethiopia, 3,300 from Nigeria, 1,600 from Somalia, and 2,800 from Bangladesh. By the end of 2016, 28,700 Somalis and 26,200 DRC nationals were living in South Africa. While many South Africans believe that African immigrants are flooding into their country, these figures are only a fraction of those received by poorer countries like Kenya and Uganda that are close to the epicenters of the conflicts in South Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, and Burundi.

The South African government’s figures for people applying for asylum in 2015 are somewhat different (Department of Home Affairs, 2017, p.29) from those of the UNHCR 2016, with 2015 figures much higher than those of 2016, but the top five sending countries are the same.

Click to enlarge.

SOUTH AFRICAN REFUGEE POLICY

South Africa’s policy on asylum seekers and refugees largely follows internationally set regimes including the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol (the centerpiece of international refugee protection).

South Africa is party to these international treaties, as well as important regional conventions like the Organization of African Unity Convention Governing Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa of 1969 and the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights of 1981.

The South African Refugees Act of 1998 and the Immigration Act of 2002 are the key pieces of national legislation (Ramoroka, 2014). Section 3 states that a person qualifies for refugee status if that person (PASSOP, 1998):

• [Fled] Out of fear of persecution for reasons of race, tribe, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership of a particular social group is outside of their country of their nationality and is unwilling or unable to give themselves to the protection of that country, or, not having a nationality and being outside the country of their former residence is unable, or unwilling out of fear, to return to it, or;

• Due to external aggression, occupation, foreign domination or events seriously disrupting public order in either part or the whole of their country of origin or nationality, is compelled to leave their place of residence and seek refuge elsewhere or;

• Is a dependent of a person described above.

Asylum seekers are likewise protected, though they are not included in the refugee definition, as long as their application for asylum has not been rejected. (Ramoroka, 2014, p.13).

Data on the legal status of migrants are incomplete, particularly for those who are undocumented. The 2011 census showed almost 2.2 million people born in other countries, including economic migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. There is also a large population of undocumented migrants (Hanna, 2016). Of

my interviewees, 22 have study permits, 8 have refugee statuses and 10 have asylum documents. For the sake of this study, the minimal benefits of finding out about undocumented status did not justify potential risks from their teachers and peers within the school and broader community. Most South Africans do not make any distinction based on legal status. They are all seen as “foreigners” or “refugees.”

South Africa does not have a policy of putting refugees in camps. Both asylum seekers and those granted refugee status settle into local communities with the right to work, study, and start businesses. However, “While the policy of non-encampment can be fully justified, there was no provision made for providing indigent asylum seekers with basic food and accommodation, leading to the courts obliging the DHA (Department of Home Affairs) to consider issuing deserving cases with permits allowing them to work or study,” (White Paper on International Migration, 2017, p.5). However, Crush (2017) argues that “the intention [of revising immigration laws as proposed in the White Paper] is to make South Africa undesirable by moving from an urban towards a border encampment model, denying asylum-seekers their current right to pursue livelihood while waiting for a hearing, and ensuring that no refugee ever qualifies for permanent residence.”

In recent years, the government of South Africa introduced special permits to regularize the stay of Angolan, Lesotho, and Zimbabwean nationals in the South African Development Community (SADC). As stated in the White Paper (Department of Home Affairs, 2017, p.18), “While South Africa continues to advocate for the implementation of these regional policy instruments in various SADC platforms, it has adopted both unilateral and bilateral approaches in removing visa conditions for SADC and other nationals outside of SADC. For instance, South Africa has implemented visa waivers, which are in line with the spirit of the Abuja Treaty with nationals of 11 of the 14 SADC countries. South Africa also implemented the Zimbabwe Special Permit (ZSP) and Lesotho Special Permit (LSP) to regularize the large numbers of Zimbabwean and Lesotho nationals residing in South Africa irregularly.”

Even those who were undocumented or with fraudulent documents were granted amnesty and given a chance to regularize their stay. Based on this gesture, I argue that South African immigration laws uphold the concept of Ubuntu. This concept is not easy to explain in a foreign language like English, but Mokgoro (1998, p.2) attempts to define it as a “philosophy of life; represents personhood, humanity, humanness and morality; a metaphor that describes human solidarity [and] is central to the survival of communities.” There is a sense of Ubuntu in these policies, trying to respect and help the broader African family by South African authorities.

APPENDIX C: REFUGEES IN CAPE TOWN

Cape Town is the legislative capital city of South Africa, and where the House of Parliament is located. It is the capital of the Western Cape Province, one of South Africa’s nine provinces. The city receives many immigrants from African countries and other parts of the world. Most are from the neighboring Southern African Development Community (SADC) member states. While most do apply for asylum on arrival, many are economic migrants fleeing hardships in the underdeveloped economies of the region (Lemanski, 2007). Among them are families, and many unaccompanied minors. The international migrants are joined by many rural South Africans coming from the Eastern Cape and other provinces.

MAPPING THE REFUGEE POPULATION IN CAPE TOWN

Stiff competition for jobs and other resources has led to vigorous local criticism of the country’s immigration model. There were outbreaks of violent xenophobia in 2008 and 2015 as locals blamed foreigners for stealing their jobs, and for escalating levels of crime. Those perceptions are encouraged by the negative coverage of foreigners in the press and populist pronouncements by politicians. Clarence Tshitereke calls this the “frustration-scapegoat” attitude by the locals toward foreigners (IRIN, 1999). In the aftermath of the xenophobic attacks some African immigrants opted for safer areas outside the townships, which were the epicenters of the outbreaks.

(Blue) The areas of Maitland and Parow where there are many Zimbabwean and Congolese immigrants, and Bellville, where the Somali community is concentrated, all located along the historic Voortrekker Road (Orange) The periphery township of Dunoon (Red) The periphery township of Khayelitsha.

Townships like Khayelitsha and Dunoon, located at the peripheries of Cape Town, are low-income, mixed housing (including informal housing, shanties, and untarred roads) areas, mainly populated by black South Africans, and where most foreigners would rather not live for fear of xenophobic attacks. The Congolese, for example, are concentrated in predominantly mixed-race suburbs like Parow and Maitland. Somalis are clustered in another such suburb, Bellville, which is nicknamed “Little Mogadishu” or “Som Town.” These suburbs are mixed use, and provide residencies and livelihoods for migrants: “It is estimated that about 5,000 Somalis live and own businesses in the Bellville CBD, and each month about 50 more Somalis enter the area,” (Nicholson, 2011).

THE TERM TOWNSHIP

The term “township” has no formal definition but is commonly understood to refer to the underdeveloped, usually (but not only) urban, residential areas that during Apartheid were reserved for non-whites (Africans, Coloureds and Indians) who lived near or worked in areas that were designated ‘white only’ (under the Black Communities Development Act (Section 33) and Proclamation R293 of 1962, Proclamation R154 of 1983 and GN R1886 of 1990 in Trust Areas, National Home lands and Independent States). Pernegger and Godehart (2007, p.2).

The Somalis seem to prefer to cluster together for religious and business reasons, traveling to and from the townships daily where they operate tuck-shops or spaza shops (small food-selling retails). However, statistics show that Somalis are being harassed and even killed (in xenophobia-related murders) in those townships (Whittles, 2017). Congolese and Nigerians also cluster in areas away from the townships. However, Basotho, Swazis, and Zimbabweans can be found in the townships living among black South Africans. Their main integration advantage seems to be that they speak Bantu languages, which are the same family as IsiNdebele, IsiXhosa, IsiZulu, SeTswana, Venda, and others spoken locally. Therefore, they quickly adapt to speaking the local languages.