Izmir, Turkey

From Seeking Survival to Urban Revival

Photo: A waterfront park area where Syrian refugees and Turks go to have picnics, play on playgrounds, eat fresh mussels, and listen to live music performances. A Syrian family watches the sunset, looking across the Mediterranean towards the Greek islands. Many Syrians have drowned trying to reach them. Report photos by Charles Simpson.

Introduction

Between 2014 and 2016, Izmir was the last stop in Asia for many refugees from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan seeking to get to Europe along the Western Balkans route. The Western Balkan route was then the preferred route for migrants from many countries of origin. Izmir was the gathering place before the sea journey because of its proximity to Greek islands. From the islands, migrants continued to the northern Greek border, up through Macedonia, Serbia, and then into Western Europe. In 2016, Balkans police and Greek and Turkish Coast Guards began cracking down on smuggling, and Izmir became a transit city where thousands of migrants were stuck, unable to afford the escalating cost of being smuggled to Europe.

This report focuses on the Basmane neighborhood of Izmir. In 2014, Basmane was the center of human smuggling in the city. Anyone could easily find the necessities of irregular migration: a smuggler, a money transfer vendor, a Turkish cell phone SIM card, and a life jacket.

Today you can also find the basic necessities of de facto integration, such as cash-based jobs with Turkish and Syrian businesses or NGOs, accessible healthcare and education services, cash assistance from the Red Crescent (managed by Turkey and paid for by the EU), and affordable housing. There are street signs in Arabic and Turkish (although official street signs are only in Turkish), Turkish cuisine and Syrian shawarma and bakeries, and apartment buildings have both Syrian and Turkish residents.

The main street leading to Basmane train station is lined with clothing shops selling life jackets marketed to Syrians about to make the dangerous boat crossing to the Greek islands.

Location

Izmir is located on the south-central coast of Turkey, only about 50 miles from the Greek islands of Lesvos and Chios, making it an ideal gathering place for migrants on the route from the Middle East, Africa, and Central Asia to Western Europe. The Basmane neighborhood is located in central Izmir near the city’s main train and bus station, as well as ferries that connect with other parts of the city.

Continue to the appendices for more information on the methods used for this report, and for background on refugees in Izmir and Turkey.

The Urban IMpact

This section focuses on how the city of Izmir, especially the neighborhood Basmane, has been changed by the presence of Syrian refugees including the demographics, the kinds of businesses and work available, and the response of the Turkish government.

Mapping the Refugee Population

Refugees first came to Basmane in 2014-2016 to find smugglers. It was easy to find temporary housing here while waiting for the next boat to Greece. The boats took off from nearby coastal towns like Ayvalik, Dikili, or Chesme. Basmane is home to a diaspora of Arabic-speaking Turks and it has a low cost of living.

However, since the Balkans Route closed, Syrians have had to look for longer-term housing in Izmir. Refugees are settling into areas of the city like Zeytinlek, Karibaglar, and Buça which offer affordable housing, are near to the city center, and near to services provided to refugees.

Districts with a large population of Syrian refugees are highlighted in yellow. They were originally attractive because they were near to smugglers, but now are preferred areas because of the low cost of rent and proximity to services. The Basmane neighborhood is named for the Basmane Gari train station and sits within the administrative district of Konak. Zeytinlek is a cluster of streets bordering Konak but within the southwestern corner of the administrative district of Bornova.

Base map image from Emirr, Creative Commons.

Karibaglar is popular because of its low rent. Basmane has slightly more expensive rent but refugees prefer Basmane because it is centrally located and nearer to aid centers.

Karibaglar and Buca are organized and neat, with mixed housing. Expensive high-rise apartments for 600-800 Lira (USD 112-150 per month) where Turks live are interspersed with older buildings with rents around 400-600 Lira (USD 75-112), where both Turks and Syrians live.

The Impact on Izmir’s Housing Stock

Refugees have increased housing demand, and each year since 2014 rents have gone up at least 25 Lira (USD5) or as much as 200 Lira (UDS37) in some apartments. There is a shortage of affordable housing, and no space to build new affordable apartment buildings. Prices for food, transportation, medicine, and other goods have remained much the same.

Zeytinlik is a clean neighborhood with low rents and is close to Basmane center, but some Syrians don’t like the Roma people who live there. Also, Zeytinlik is a mixed-use neighborhood, so apartments share the street with auto repair shops and other businesses. Zeytinlik was once a low-income area but has been rejuvenated by Syrian immigration. These neighborhoods have the most Syrians, but Syrians now live in almost every neighborhood in Izmir because the city’s public transit is good enough to cover the distance between work and home in reasonable time. Alsancak is the expensive downtown area. Only a few Syrians live here, usually groups of men splitting 1,200 Lira (USD 225) rent amongst the group to share one apartment. Other wealthy neighborhoods are mostly Turkish.

Making Rent

By far the biggest monthly cost is apartment rent, so this is a main factor determining where refugees live. Turkish landlords are generally kind but inflexible: If you can’t pay rent or utility bills you can’t stay. Some tenants are able to borrow from foreigners or relatives, but others end up homeless when they can’t pay their bills. Then young men might sleep in Kulturpark, a public park near Basmane, sometimes getting food from sympathetic Syrians.

Many refugees live in tented camps on rented land up to 50 km outside Izmir, such as in Manisa and Torbali. These refugees are from the countryside and prefer tribal life where they can work in agriculture, live in communal settings, and keep animals. These groups are semi-nomadic and move seasonally depending on crop and pastoral rotations.

Public Parks

Izmir has many public spaces including, parks and the waterfront area that allow mixing and socializing between refugees and Turks.

Afghan people are required to live in camps in Manisa and Mugla, or risk being returned to Afghanistan. Some still find a smuggler to go to Greece. Afghan students are the exception since they can apply to university if they have proper paperwork for residency.

Local Economic Impact & refugee Livelihoods

A large part of refugees’ economic impact comes from remittances going out and coming in. Many people send money back to Syria, but money is also sent to Izmir by relatives in Europe and the Gulf. Between 2014 and 2016 refugees in transit spent their savings – mostly on smugglers, but large amounts also went to Basmane’s restaurants, clothing stores, internet cafes, cell phone shops, hotels, money transfer shops, and grocery stores as refugees waited for their boats. After 2016, as refugees began to settle in Izmir, they spent money on other goods and services in Basmane, Zeytinlik, Karibaglar, and Buca. They began renting apartments, buying more groceries, medical supplies, clothes, and began spending more on regularly used services such as Arabic-Turkish translators, money transfer vendors, and internet cafes.

Clothes Shopping for Smuggling

Clothing stores made money selling shoes, shirts, and pants to migrants, but also exorbitant profits by selling life jackets to those who were crossing to Greece by boat. These shops still have special back rooms and basements for these items even as Mediterranean migration has slowed.

A shopping area in Basmane where one can find Syrian barber shops, grocery stores, vegetable and fruit vendors, electronics stores, cafes, restaurants, money transfer vendors, and smugglers.

While some Syrians who planned to stay in Turkey had already found work, those who wanted to go to Europe did not pick up jobs until 2016 when it was clear the Balkans route would remain closed. At this point, these Syrians had to find jobs as their savings began to run out and they could not travel onward. Only a few refugees with good connections to a wealthy family can continue to live off savings. For example, I know one Iraqi refugee who works as an artist and volunteers while living in a high-end street of Karsiyaka because his sister sends him money each month.

Those without connections to rich people may become homeless before they find work. There are many low-skilled, cash-based jobs in Izmir’s informal economy where people work long hours for little pay. Often Syrians start with these jobs. Most Syrians are underemployed: for example, college-educated Syrians work as dishwashers. Most earn 900-2,500 Lira (USD 168-465) per month doing jobs in tailoring, clothing manufacturing, or working in restaurants and cafes. A few refugees work as doctors, earning at the high end of the spectrum, near 2,500 Lira (USD 465). Syrians also work as fixers, translators, or drivers for the numerous aid organizations in the city. For example, many of IOM’s employees are Iraqis and Palestinians. While working at NGOs, some study at Turkish universities on the side to advance their careers.

Even smugglers have had to find legitimate jobs in Izmir, since they no longer make money sending people to Europe and have spent all their money on luxury items. They can be seen working in construction or in restaurants, still calling to people walking by that they can find them a way to Europe.

Refugees usually are in debt to friends and family who loaned them money to reach Turkey and continue to support them while they are there. Smugglers were generally paid in advance.This debt may be thousands of US dollars. There is also social debt to family and friends in Syria, so that even poor Syrians will send money back home. Money can be sent by Western Union to Europe but not to Syria. People use informal money senders (hawala), but the Turkish government has tried to crack down on them. Many Syrians have lost trust in the informal money transfer system because there have been problems with theft.

Response of the Turkish Government

There are few legal obstacles to Syrian refugees accessing jobs or educational opportunities in Izmir. Work permits are easily available for all nationalities with the employer’s approval. Enrolling Syrian children in schools is also now an easy process.

However, the government has imposed a number of restrictions on international humanitarian organizations in Turkey. First, the government requires agencies to pay fees to work in the country, which are prohibitively expensive for some organizations. Second, the Turkish government requires that all aid be implemented through the Turkish Red Crescent, and laws require aid organizations to have Turkish oversight and a high ratio of Turkish to foreign employees. Team International Assistance for Integration (TIAFI), a European privately-funded aid organization in Izmir, was accused of violating the law that requires it to hire five Turkish employees for every one Syrian employee. This was not possible with their funding limitations; they have nine Syrian hires, so were ordered to shut down if they could not hire 45 Turkish employees.

The Turkish government is concerned about Syrians being too expensive for the city’s healthcare and education services. Cash assistance for Syrians is run through the Turkish Red Crescent, funded by the EU, and implemented through a digital charge card. Families receive cash assistance depending on their health conditions, number of children, and other factors. On average, a family receives around 130 Lira per person per month (USD 25). Since summer 2017, disabled refugees, children under 18, and elderly people receive about 150 Lira (USD 27) per month to help cover medical costs.

The cash assistance is not enough for most families to live on. Most families receive 500-700 Lira (USD 128) per month but pay around 400 Lira (USD 75) for rent and 500 Lira (USD 93) for food. There are additional expenses for medicine and children, costing them an additional at least 200 Lira (USD 37) each month. This means income from work and local aid organizations that provide food, baby formula, and clothes are really important (see section, “Accessing City Services”).

Until 2017, children needed a Turkish ID from the province they were originally registered in (often Hatay or Istanbul) to register in schools, but this made it difficult for children to get into school until the policy was changed to allow non-Turks to enroll children directly. Each month Syrian children get 35 Lira (USD 6.5) on a charge card to go to school, but if the student does not show up at school for four consecutive days, this is cancelled.

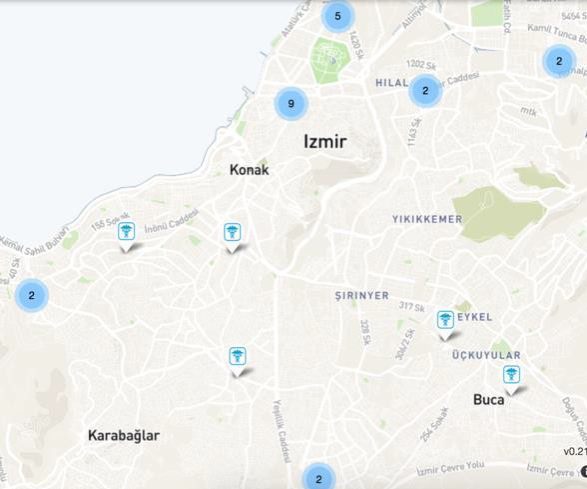

There are three government cash assistance distribution offices in Izmir, two in Basmane (left) and one to the east in Buca (right). Both of these are low to middle income neighborhoods were many Syrians reside.

Source: UNHCRServicesAdvisor.org

Social Integration

Turkish people in my neighborhood were kind and neighborly. The culture is similar to Syria’s and the city layout is familiar. The city reminds me of Damascus. The Turkish government does not bother Syrians, and Turks and Syrians are usually Muslim, so religious events, mosques, and holidays are similar. Children play in the street and go to school, people have picnics, and they go to work. Services are available to refugees, including public school enrollment and scholarships for university. In my experience, hospitals treat refugees as they would a Turkish person.

Child Labor

In some parts of Syria, child labor is still considered normal. It is usually Western aid workers in Izmir, not Turks, that pressure Syrian parents to send their children to school rather than working. Parents are incentivized with extra cash for a school stipend from the Turkish Red Crescent; as long as their children do not miss four days of school in a row they will continue receiving the stipend.

Turkish Attitudes

Some negative attitudes arise from Turks’ concerns about Syrians taking jobs. Syrians will accept pay rates that Turks will not, and then Turks feel angry. Some Turks would say to me: “You took our jobs, you took our money, you took our food,” but they were usually kind even if they were troubled by these problems. In my two years in Izmir, I only met one Turk who was mean. In an expensive area of the city at the seaside, he said to me: “This is not your country, you should return to Syria,” but then he was shooed away by my friends.

Maintaining Connections to Home

Refugees talk with their families back in Syria, with other Syrians in Turkey, and with Syrians in Europe through social media. Sometimes Syrians visit relatives or friends in other towns across Turkey, but these towns are distant, and this usually only happens once or twice yearly. Syrians miss their families and friends. I see many people crying, especially during Ramadan and Eid (Islamic holidays). Social media connections are important for keeping relationships alive and maintaining emotional health, and this helps integration.

Getting Past the Language Barrier

The primary challenge for refugees is the language barrier. Some people work through the problem by learning Turkish; Red Crescent also offers classes around the city. In Basmane, a local community center offers free classes. Others work around the problem by only interacting with other Arabs and choosing to send their children to Arabic language schools.

I tried joining a class at a local NGO called Kapilar, but the teacher didn’t always show up, so I left and ended up learning Turkish from people—especially children—I talked to on the street and my neighbors. I learned Turkish well, my brother learned a little bit, and my mother did not learn any. She did not want to learn Turkish because it was not familiar to her (now, she is in English intensive language classes here in Canada, and she remembers some from when she was in school learning basic English in Damascus).

Basmane’s mix of Syrians and Turks gets along pretty well. All are low to middle income, and connected by their economic standing, as well as religious customs.

Almost as important as knowing Turkish is knowing English. Because I spoke English, I met people of different nationalities, which opened up job opportunities. I worked as an English translator, a social aid worker, and researcher for NGOs. I learned new vocabulary including medical and legal terms in English and Turkish through an iPad I was given by a Western aid worker.

My Experience Learning English

I originally learned English because in Syria when I was 15, I studied in an American school in a program called Amideast. The war between Israel and Lebanon in 2006 caused problems between the U.S. and Syria, and they closed the U.S. embassy in Damascus and cancelled the Amideast program. After that, I stopped studying English and went to a Syrian University where courses were in Arabic, but I liked languages and kept learning English through music or TV. My oldest brother also learned English in a private school; now he’s a journalist. In Lebanon there was a church that gave English classes, but I stopped going there because they tried to convert us to be Christians.

Integration into the education System

There are both Turkish and Arabic language schools in Izmir. Families choose which school to attend based on personal preference. Some parents see Arabic schools as a way to preserve their culture and their children’s connection to their homeland, while others see Turkish schooling as an advantage to open up job opportunities or prepare their children to attend a Turkish university. A middle path is to go to an Arabic school that provides Turkish language classes. There are many of these schools in the neighborhoods where refugees live, including Buce and Konak.

Textbooks are mostly in Turkish, and the curriculum is in accordance the Turkish educational system. Teachers in Turkish schools are mostly Turkish nationals with a few Arab teachers to help with students who do not speak Turkish well, while teachers in Arabic schools are mostly Arabs from the Syrian opposition. Syrian and Turkish children get into arguments, and “Soori” (meaning “Syrian,” in Turkish and Arabic) has become a slur used by against Syrian students. This kind of discrimination is not new: Syrian children in Damascus used similar slurs to refer to Palestinian students there. I mostly see this as the kind of bullying kids do everywhere, and not that big of a deal. Kids seem to get over it and Turkish and Syrian children play together all the time. If children don’t go to school it is because their parents want them to work, not because they were bullied.

Accessing City Services

Syrians receive medical care, education and a small cash stipend each month, and for the rest of their expenses and needs they seek out help from each other. For example, people find housing on their own. When I first came to Izmir I stayed in hotel where the smuggler took us while we waited to be smuggled to Greece. After the police stopped the smuggling, we had no money left, so we found an apartment through a realtor.

A meeting of local civil society organizations in the Basmane neighborhood outside of Kapilar is well attended by resident Turks as well as Syrians.

Food, clothing, and other goods are usually provided through local support in the neighborhood, not by the government. Sitting outside a Syrian restaurant, I was given a wheelchair by a Lebanese resident. Some international people helped with rent or gave me market charge cards. Two organizations that helped me were Mercy Corps and a small local NGO in Basmane called Kapilar. This organization gives out things donated by the international community and local Turks like clothing and food. They also give free language classes in Turkish and English taught by a mix of Turk, Syrian, and international volunteers. Most importantly, Kapilar helps connect people. Through meeting people at Kapilar, Syrians find jobs and get useful information like where to get affordable furniture, what hospital to go to, and when the next distribution of food donations will be. People can even sign up for door-to-door deliveries where volunteers drop goods off at their apartment when things become available. Through Kapilar I met the Canadians who sponsored my resettlement.

An Arabic sign advertises a saraf, or money transfer shop which sends funds across the Arab region, Turkey, and Europe through informal networks. In the background is Basmane Gari, the train station that gives the neighborhood its name.

These local organizations are very different from the services offered by the Turkish or Izmir municipal government, which, still today, many people don’t know about. Internationally-supported organizations like the Red Crescent provide more consistent services (for example, Red Crescent rarely runs out of supplies like baby food, while local organizations like Kapilar had frequent shortages), but refugees may not know about the services offered by large organizations, or what rights they have. I could speak with international organizations in English, and many Syrians relied on me to get information. For example, UNHCR has a map of all of the service locations in Izmir, but I only found out about this map last year after interviewing an aid worker for this report. Most Syrians don’t know about the map. By comparison, people find out about local community services like Kapilar by word of mouth, and everyone in the city knows about them.

UNHCR has a digital online map of services including healthcare, food and cash distribution, and shelter available across Turkey in Turkish, Arabic, and English. However, most refugees in Izmir have never heard of this map and rely on informal word of mouth to locate services.

Kapilar was also different from certain international NGOs who, in my experience, didn’t do good work, stole donated money, and were corrupt. They demanded long hours of their Syrian workers for little or no pay. Some are run by foreigners who don’t speak Turkish or Arabic or even English in some cases and have no ability to communicate with the people they are supposed to be helping.

Since 2015 the Turkish government has sought to reduce the number of INGOs and their influence, fearing they will undermine the government, empower the opposition, and take services and funding away from Turks in favor of foreigners. The Turkish government rarely explicitly requires INGOs to close but will set impossible to achieve requirements like having a large number of Turkish employees, or simply delaying written authorizations until the organization has to shut down. Many INGOs have left, and several have begun operating under the authority of registered Turkish umbrella organizations.

For example, Kizlay is the organization that hands out cash cards, but they are working under the authority of the Turkish Red Crescent. Mercy Corps and other organizations were shut down when the Turkish government restricted access of INGOs. Although Mercy Corps was helpful, in my experience this has been overall a good thing, because it got rid of many of the problematic INGOs. The Turkish Red Crescent and other organizations that remain are kind and not discriminatory.

Accessing Healthcare Services

Hospitals in Izmir are crowded, and one has to wait a long time (Although to my surprise, I have to wait even longer in Canada on medical appointments!). Most doctors speak English, but sometimes I had to bring a Turkish friend with me to help translate medical words.

There are numerous medical centers across Izmir, but the waits are long, and virtually no medical professionals speak Arabic, requiring volunteers to accompany refugee patients. Map image from UNHCR Services Advisor Client.

In Turkey, you can find treatments for basic medical conditions like insulin for diabetes, and costs are affordable though wait times are long. However, more advanced treatment is often not available, as in my case. I found a local organization with a volunteer physical therapist who helped me regain my strength.

The biggest untreated health issue among refugees is mental health. We feel so much stress, anxiety, and fear for family back in Syria. There are many psychological treatment services and behavioral health specialists available, but most Syrians don’t access these services even though they know they are having psychological problems. They think seeing a therapist is only for “crazy people.”

Conclusion

Many Syrians want to stay in Izmir even after the war ends and are trying to achieve Turkish citizenship. Citizenship is attainable after living in the country for five years if you have learned to speak Turkish fluently, with the priority given to well-educated people. One neighbor in Basmane, a middle-aged Syrian man who lives with his wife and three children, really likes Izmir and wants to get Turkish citizenship. He works as a carpenter alongside Turks, continues to improve his Turkish, and has a good apartment. Even if the war in Syria ends, he says he won’t go back.

However, another man from a similar family in Basmane told me he doesn’t like Izmir and wanted to leave. He complained that he didn’t make enough money as a tailor, and that their house wasn’t acceptable since it was lower quality than what he had in Syria. He has barely learned any Turkish and is trying to leave. The UNHCR told him he is not an urgent case when he applied for resettlement, so he is talking to smugglers and internationals who might sponsor his international resettlement.

I felt no discrimination in Izmir and liked living there. But I decided to leave because I needed medical treatment and a high-quality education. Looking back, I see the advantages and disadvantages of living in Izmir. Even though we worried about rent each month and our apartment was cold in winter and hot in summer, I preferred Izmir’s crowded bustle, meeting so many different people and finding work with aid organizations. This quiet little town in Canada is so different, but I’m here for my treatment and my educational future.

Basmane has been transformed by its Syrian population. This is the main square, with a Syrian sweet and food shop, a Turkish seafood restaurant and a Syrian shawarma shop all displaying their names in Arabic and Turkish. Further down the road are Syrian and Turkish barber shops, vegetable stalls, tea and shisha cafes, electronics stores, and clothing shops.

Noor Falah Ogli

Izmir, Turkey

Noor studied law at Damascus University before moving to Lebanon, and then to Turkey when the war in Syria started. In Izmir, Turkey, she volunteered as a translator and liaison between refugees, government representatives, INGOs, and service providers for multiple organizations including international news media, Kapilar (a local civil society organization), Mercy Corps, and the Turkish and International Assistance for Integration (TIAFI). She currently lives in Canada.

Email: noorfalahogli@gmail.comReferences

Biondich, Mark. The Balkans: Revolution, War, and Political Violence Since 1878. Oxford University Press, 2011.

Directorate General of Migration Management, DGMM. (2017). “Migration Statistics on Temporary Protection.” Available. Online: http://www.goc.gov.tr/icerik6/temporary-protection_915_1024_4748_icerik

Icduygu, A. (2015). Syrian Refugees in Turkey: The Long Road Ahead. Migration Policy Institute.

Izmir Chamber of Commerce. (2018). “Economy of Izmir.” Online. Available at: http://www.izto.org.tr/en/

Jacobsen, K. (2001). The forgotten solution: local integration for refugees in developing countries. UNHCR, New Issues In Refugee Research, Working Paper(45).

Koru, S., & Kadkoy, O. (2017). The Influx of Syrians in Changing Turkey. Turkish Policy Quarterly.

Republic of Turkey. (2018). “Turkey: Provinces and Major Cities.” City Population Census. Online. Available at: http://citypopulation.de/Turkey-C20.html

UNHCR. (2019). “Services Advisor: Turkey.” Online. Available at: https://turkey.servicesadvisor.org/#/

UNHCR. (2018). “Turkey Inter-sector dashboard.” Online. Available at: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/dataviz/38?sv=4&geo=113

Watson, I., Karci, I., & Bilginsoy, Z. (2015). “Syrian Refugees Swarm Turkish Port City.” CNN. Online. Available: https://www.cnn.com/2015/09/08/middleeast/syrian-refugees-turkey-boats/index.html

APPENDIX A: METHODS

The report is based on unstructured conversations with Syrians, Turks, government representatives, aid workers, international humanitarian personnel, and my own experiences having lived in the Basmane area of Izmir for two years. For this report, I spoke to 47 individuals about their experiences in Izmir, including 30 low-income and minimally educated Syrian refugees, half men and half women, working as seamstresses, clothes sellers, or dishwashers. Several were very poor, washing cars on the street for tips, or collecting plastic to earn garbage collection money. All of these individuals are supported by the Turkish government through a Red Crescent card, funded by the EU.

During this process refugees register with Red Crescent who then confirms their identity, address, age, disabilities, and family size through home visits and interviews. Within 15 days the Red Crescent will make a decision on eligibility at which point a refugee picks up their card from one of their service centers. This card is refilled with credit every month and works on Halk Bankasi ATMs, allowing a refugee to withdraw cash – it does not allow digital transactions. Turks with disabilities, old people, the unemployed, and single parents receive welfare from the Turkish government that allows them to meet their basic needs.

I also talked to middle-income Syrian refugees who work as mechanics, smugglers, in construction, at desk jobs, as tailors, own bakeries, manufacture fabric, or work with Turkish partners managing restaurants. They often relied on savings from being business owners in Syria to get their new careers started in Turkey. The women usually didn’t work. I did not speak to any high-income Syrians or Turks in Izmir. Almost everyone who was high-income in Syria is now middle-income in Turkey, having lost their businesses and spent their savings on smugglers. High-income Syrians are usually traders who had import-export businesses in Izmir before the war in Syria broke out. The high-income Turks in Basmane are business, hotel, or apartment building owners, involved in shipping, business partners with Syrian smugglers, or involved in banking and finance.

My interviewees came to Izmir at different times. Most Syrians came after 2012, but four had been here before the war. Two were Syrian young men who had come to study at university and have since graduated and found jobs; you now can’t tell that they are Syrian when they speak Turkish because their pronunciation is so close to that of local native speakers. The other two worked for a Turkish business and stopped going home when the war started. The people I talked to were between the ages of 18 to 65. There were many children in the neighborhood too. They played in the street around my apartment and a nearby NGO that offers child care. I include my observations of their experiences in the section on Turkey’s education system.

I talked to non-Syrian migrants including five Palestinians, one Algerian, one Iraqi, one Moroccan, and one Tunisian, all of whom tried to go to Europe through Turkey’s smugglers but got stuck in Izmir. The exception was a Yemeni woman who came to Izmir to study medicine and began working for a volunteer organization once refugees started arriving. I also regularly observed Asian migrants including Afghans, Pakistanis, and Iranians. In Izmir there are also many Western migrants who came as journalists or volunteers, including Americans, Canadians, and Europeans. These Westerners became a source of income for many non-Western migrants, but also a source of tension with the Turkish government because of problems with nepotism, corruption, and lack of sensitivity toward Turkish laws.

I spoke to representatives from aid organizations including the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the Red Crescent, the Association for Solidarity with Asylum Seekers and Migrants (ASAM), and a local NGO called Kapilar, in my neighborhood. I worked for five organizations over two years, and these experiences inform my report. I also spoke to representatives from the Turkish government and public services offices including the refugee registration office, hospitals and clinics serving Syrians, dentist’s offices, and school administrators. I did not speak with any police for this project, but I do regularly see them around Basmane, and interacted with them when I first arrived in Turkey.

The Author’s Position in Izmir and Experiences Researching this Report

My name is Noor, which means "light" in Arabic. I am Palestinian, but I was born and grew up in Damascus, Syria, where I went to school and university. Governments in other countries don’t deal well with Palestinians who face much discrimination, but the Syrian government was good to us. I felt like Syria was my country, I didn’t feel like a refugee there. The Palestinians in Syria are well educated and can work. However, they cannot vote or take certain government positions.

I couldn't finish university in Damascus because of the war: a bomb exploded at my university. The first time I left Syria I went to Beirut, Lebanon, but the cost of living was too high, and Syrians face a lot of harassment there. Every three months we had to renew our permanent residence permit and pay fees. The situation was miserable, so I left. I went back through Syria, then travelled to Turkey as a refugee with my mother and brother. I wanted to go to Europe by boat, so I could continue my education and get medical treatment, but we were not able to complete that dangerous crossing. After three frightening failed attempts to get to Europe by boat, I decided to find another way to follow my dreams to complete my education and become healthy again.

I settled in Izmir in 2016, close to the port from which our boat had attempted to take us to Europe. It was not easy, but eventually my family and I found an apartment in Basmane. I worked hard to create a good (but temporary) life for my mother, brother, and myself. I achieved intermediate-advanced level English and Turkish and I found work as a translator and fixer for international non-governmental organizations. I also worked or volunteered for NGOs (including Kapilar and REVI), journalists, and researchers by helping them connect with refugees around Izmir.

It was not difficult researching the RIT report. As a Syrian, I spoke mostly with other Syrians and Turks both in offices with employees, and in informal conversations. People wanted to show that Izmir is an open city, to Syrians, to Afghans, to everyone.

I needed medical treatment that was not available in Turkey. The doctors were very kind and helped with physical therapy, but I needed more advanced treatment, so I applied for resettlement through private sponsorship to Canada. After years of waiting, in July 2018 I was resettled in New Brunswick, Canada, with my mother and brother. When I was 18 in Damascus, I wanted to go to Canada. My mother has cousins there, and I was dreaming I would go study abroad. Maybe if the war didn’t happen, I wouldn’t have come here.

Appendix B: Refugees in Turkey

In the early stages of the Syrian conflict, Syrian refugees mostly clustered in southern Turkey close to the Syrian border. However, as the protracted nature of the crisis became apparent, they began to move to big cities such as Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir. The most recent Syrian refugee wave to Turkey started when 252 Syrians arrived at the Turkish border on 29 April 2011, following the Syrian government’s crackdown on anti-government protests. In the following three months, there were some 15,000 border crossings. As a preliminary measure, refugees were taken to a shelter area built in Hatay province on the Syrian border. The first group of arrivals mostly consisted of young activists, oppositionists, and protesters, and almost half of them went back to Syria by the end of 2011 (Icduygu 2015).

Forced migration regained momentum in 2012 as ceasefire talks between the Syrian government and the opposition failed. Turkish authorities responded to the increasing numbers of refugees with unofficial measures: additional tent cities were built in provinces including, Sanliurfa, Kilis, Osmaniye, and Gaziantep on the Syrian border (Icduygu 2015).

While Turkey is a signatory to the 1951 Convention, it maintains a geographical limitation in that it only grants refugee status to asylum seekers who are displaced “due to events unfolding in Europe.” Therefore, Syrians who were welcomed by the Turkish government as “guests” did not initially have any legal protection status (Koru & Kadkoy 2017).

It took two years from the initial arrival of Syrian refugees in 2011 for Turkey to make legal adjustments. In April 2014 two major developments were enacted. First, the Department General for Migration Management (DGMM) was established to fix the lack of coordination among the institutions working on migration and asylum. Next, Parliament passed the Law on Foreigners and International Protection (LFIP) which granted temporary protection to Syrians and provided access to basic public services such as health, education, and to a limited extent, the labor market (Koru & Kadkoy 2017).

As of the last available data in 2017 there are 3,523,981 Syrian refugees in Turkey, 92% of whom live outside of camps (DGMM 2017). Refugees have at least three reasons to prefer life in non-camp urban settings.

First, almost all the 23 refugee camps in Turkey are operating at maximum capacity. Second, refugees can find better shelter in the cities through family ties or by using personal financial resources. Finally, cities provide opportunities for higher mobility with less surveillance by the Turkish security apparatus.

APPENDIX C: REFUGEES IN Izmir

Izmir is a large Turkish city on the Mediterranean coast housing more than three million people (Republic of Turkey, 2018). It is politically liberal, and economically vibrant, with the main industries being manufacturing—especially of textiles and metalwork—and shipping, with the city’s Port of Alsancak responsible for a fifth of all Turkish exports (Izmir Chamber of Commerce, 2018).

Izmir became world famous in 2015 as the last waypoint of Syrian refugees before they launched on boats from nearby fishing towns on their way to the Greek islands, only a few miles away from the Turkish coast (See for example Watson, Karci & Bilginsoy, 2015). However, as the Western Balkans Route was closed off by efforts from EU Frontex, the Greek Coast Guard, the Turkish Navy, and the Turkish Gendarmerie, migrants became stuck in Izmir.

They initially settled in the smuggling hub of Basmane, but eventually spread out across the city, transforming the businesses, housing market, and services of almost all middle- and low-income neighborhoods of the city. Syrians have come to Izmir from other parts of Turkey like Urfa or Istanbul because they could not find work in those cities and could not afford the high cost of living there. Today, there are some 200,000 Syrian refugees living in Izmir (UNHCR, “Turkey Inter-sector Dashboard,” 2018).

Most refugees in Izmir are from Aleppo because of its proximity to Turkey. By contrast, refugees from the south of Syria tend to go to Lebanon or Jordan, because of its proximity. However, since Jordan closed its border in 2016, many Syrians from southern cities like Dara’a have started traveling north, even though ISIS controlled territory, to reach the relatively porous Turkish border controlled in large part by Kurdish militias. Syrian refugees in Izmir live among many other migrants coming from the Arab world (such as Iraqis, Palestinians, Tunisians, and Algerians), Central Asia, and a few from sub-Saharan Africa. Populations of refugees are a mix of families, women or single mothers whose husbands were killed, young single men escaping the Syrian military draft, and elderly people who fled when their families were killed.

There were also some Syrians in Izmir even before the war started, having worked as traders in Izmir’s port, shipping goods between the Syrian coast from towns like Latakia onward to Europe. Other pre-war Syrian arrivals to Izmir included college students who learned Turkish and have since found good high-skilled jobs in the city.

Izmir’s history of hosting forced migrants goes back long before the arrival of Syrians. In the early 1900s, the city was called Smyrna, and was part of Greece, composed of a mixture of ethnic Greeks and Turks. In 1922 however, Ataturk retook the city, and set the Greek and Armenian parts of the city on fire, killing at least 10,000 people, and forcibly displacing the remaining non-Turks (Biondich, 2011). Syrian refugees are then only the latest migrants transforming the city; this has been going on for centuries.